Designing a mobile stretcher to transport patients to healthcare workers through the terrain of South Africa’s townships.

MIT D-Lab class

Student team

MIT student unless otherwise noted.

- Jason Chen ’25, Mechanical Engineering and Literature - Jason is a 3rd-year MIT mechanical engineering student interested in the intersection of thermal-fluids engineering, computation, and sustainability to develop climate change technology.

- Kemi Chung, ’25, Mechanical Engineering - Kemi is a 3rd-year mechanical engineering student at MIT, concentrating in robotics and biomedical engineering

- Michela Galazzi, ’25, Massachusetts College of Art and Design, Industrial Design - Michela is a 3rd-year industrial design student at MassArt with an interest in product design.

- Maddie Johnson-Harwitz, ’25, Massachusetts College of Art and Design, Industrial Design - Maddie is a 3rd-year industrial design student at MassArt with an interest in product design.

- Malachi Macon, ’25, Mechanical Engineering - Malachi is a 3rd-year mechanical engineering student at MIT, concentrating in robotics.

Community partner

Location

Johannesburg, South Africa

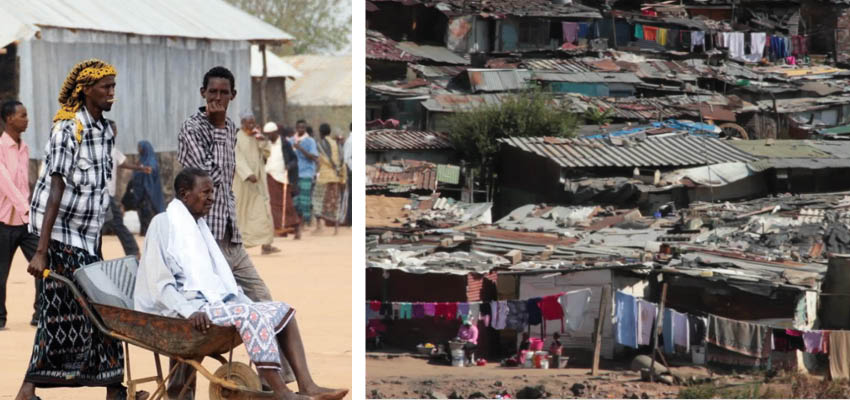

Problem

The public health system in South Africa is not built to serve the entire population equally. In the townships of Johannesburg, South Africa, a significant obstacle for patients requiring prompt emergency care is the challenge emergency vehicles face in accessing them quickly. The townships are underdeveloped and lacking infrastructure, with unpaved roads and rough terrain that makes it impossible for emergency anywhere but the outskirts of the settlements. Thus, for patients to reach emergency vehicles, they need to be carried or transported to the nearest main road in makeshift stretchers or wheelbarrows. These current solutions are dangerous, pose additional health risk, and are undignified for the elderly, pregnant women, and young children that require medical attention. To bridge this gap in healthcare inequity, a mobile stretcher that can be stored in the township homes is needed to transport patients to ambulances through the densely populated areas with rough terrain.

Cultural context

The townships of South Africa were established during the apartheid era as segregated residential areas designated primarily for non-white inhabitants. These townships were systematically underfunded and lacked adequate infrastructure, a legacy that has continued to affect the socio-economic conditions and health inequities within these communities long after the end of apartheid in 1994. Currently, the healthcare system in South Africa lacks infrastructure for low-income densely populated urban eras and does not service them equally compared to wealthier regions. Existing stretchers on the market are expensive, require excessive training, and are not maneuverable enough for the narrow strips in the townships. Our community partner, Lebo Molete, is starting a volunteer first-aid assistance program in the townships that will help transport patients to emergency vehicles but is looking for a solution to the stretcher design problem.

Proposed solution

The proposed solution is to design a mobile stretcher to transport patients to larger roads accessible by an ambulance that can withstand difficult terrain, and be highly portable, easily maintainable, and storable. The current prototype features a three-wheel design with hinges to fold the stretcher for storage and removable wheels. Initial testing has shown good stability and iterations are being made on the wheel placements and design for improved maneuverability and better user experience. We have experimented with two types of padding using foam and weaving nylon niwar strips. An important aspect of the maintainability of the stretcher is the ability to clean the stretcher with a hose after each use to wash off any contaminants and fluids. Thus, our padding solutions are designed to be waterproof. Our goal is to prioritize design criteria that will enable an initial prototype to be manufactured and tested on site in the townships to gather actual user feedback for future iterations of this project.

Next steps/future work

The next step needed to integrate this stretcher design into the township communities is to manufacture a prototype in South Africa with the connections our community partner Lebo has. Initial testing will give real user feedback that can be used to iterate on the existing design to further improve its utility and user experience. A possible partnership with Dr. Peter Oviroh, a mechanical and electrical engineering professor at the University of Johannesburg is also possible if future travel to South Africa is done to test the stretcher design. As an immediate next step, we are communicating our design findings to our community partner and providing him with tthe key learnings from the iterations we have done.

Contact

Ankita Singh or Eliza Squibb, Co-Instructors Leadership in Design