In April of last year, members of the MIT community gathered virtually to celebrate the 19th annual IDEAS Awards presented by the PKG Center for Public Service. IDEAS is MIT’s social innovation challenge and has been bringing MIT students together with mentors from industry, academia, and community organizations to tackle pressing social and environmental issues through innovation.

One of the recipients of the IDEAS juried grants was the TILT project: a low-cost wheelchair attachment that allows assistants to pull wheelchair users and their wheelchairs up and down stairs more easily and safely in areas that lack accessibility infrastructure.

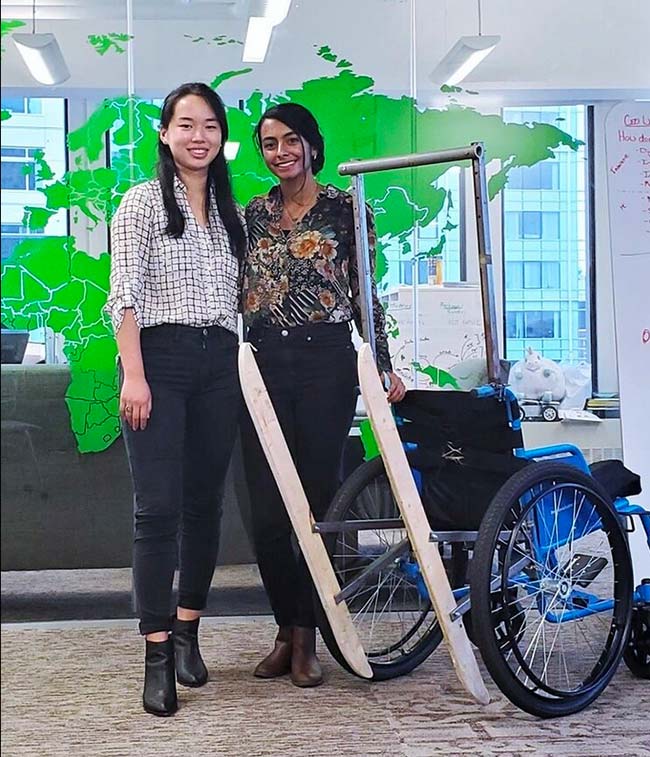

The TILT team comprises Smita Bhattacharjee, Jessica Xu, and Nisal Ovitigala; three MIT seniors in Mechanical Engineering with shared passions for user-centered design and assistive technology. Jessica and Smita met while working together through SMURF (Singapore-MIT Undergraduate Research Fellowship) over the summer of 2018, then again in the D-Lab: Development class that fall. “We realized we have this shared interest in applying MechE to serve underserved populations and affect global health and accessibility, and we decided to take TILT forward,” explained Jessica.

Towards the end of 2019, the two-person team expanded to include Nisal - a student from Sri Lanka with a new perspective and slightly different background. “It’s hard to find projects where people are willing to put in the time and effort to help someone, where you don’t really see the immediate impact,” he explained. “I just enjoyed their passion and vision, and I knew I wanted to be part of this team.”

TILT started as a D-Lab: Design class project, where a team of MIT students including Smita were given a problem statement by Professor PVM Rao of the Assistech Lab at IIT Delhi: Developing countries lack accessibility infrastructure, and in India, less than 3% of buildings are wheelchair accessible. The team at IIT Delhi did the initial user research and scoping for accessible technologies, while the D-Lab team came up with a prototype that could fit the constraints they had worked out with their community partners.

“We started off trying to think of the basic modes in which you would get up a slope and might get up the stairs, so we started with ramps. Then we were thinking of modified wheels, and we just tested base technologies that all of our future designs would use learnings from,” said Smita. The team ended up coming up with a prototype that fit the constraints of being attachable, working for different stairs and different heights of stairs, and was cheap: an attachment that essentially creates a “moving ramp” for the wheelchair.

“We also looked at why other solutions were not addressing certain aspects that our users needed or were not widely used, and we understand that there was a lot that was just cost-prohibitive and impractical,” said Smita, adding, “I chose to continue [the project] partially just because I like the design challenges, and because I really believed in what we were trying to do and that it could help people.”

After tying in Jessica and Nisal, the TILT team looked to other resources at MIT that could assist with funding for materials and prototyping and mentorship. They first sought support from MIT Sandbox, which provides seed funding and mentoring for student-initiated entrepreneurial ideas, and has been a valuable source of funding and business insight for TILT since spring of 2019. The team iterated the initial prototype to significantly reduce the necessary time to attach the device to a wheelchair, improving robustness and making user testing feasible. Knowing the importance of testing out their product “on the ground”, that summer, they received MIT Legatum’s Voyager grant to travel to India for a field visit and user validation.

“It’s not just an engineering problem, where you have the constraints of the stairs and the constraints of the wheelchair, and you find something that fits those needs in the middle of those constraints,” Jessica explained. “You have social and cultural considerations. We learned more about the stigma around disability and how it’s different than what we see in the US.”

Nisal noted the value of working with Professor Rao at IIT Delhi, adding, “[He’s been] an amazing resource in advising us on how we can address not just the engineering challenges, but also the social, cultural challenges. What would it look like to actually make the device in India, and how can it be maintained? These are all the aspects we can’t really get a grasp on being in the US.”

Recognizing the social impact of their project, the team looked to IDEAS and the PKG Center for further support. “On the surface, the goal [of TILT] is to allow greater accessibility, but what is really exciting is that it enables wheelchair users to interact with their communities, go to work, or get an education more easily,” said Jessica.

“I do feel that within MIT there’s this untapped fabric of people who really care about social entrepreneurship projects,” Smita added. “There is actually a pretty nice interconnected ecosystem between Legatum, Sandbox, and IDEAS, and once you see some of these opportunities, you see the rest of them.”

Looking ahead, the team has been exploring the different pathways on which they can continue the project after they graduate by reaching out to social entrepreneurship resources, instructors, and advisors on campus, all while considering the complexities that come with making a low-cost device and making it available halfway across the world, and the lessons learned from working in the disability space.

“I’ve always been a huge proponent of user-centered design,” said Jessica. “Working on TILT first-hand has shown me that it’s not just about the immediate needs of the user, but also the social factors. Is a caregiver, assistant, or family member readily available? What is the process like for having someone help you move up and down the stairs? Overall, it’s been a really good lesson in being connected to people who know about various aspects of the space.”

“It’s not purely a design challenge,” added Nisal. “There is an end user, and we need to design the product not for our needs or for what we think works well,” he said. “We’re doing a lot of redesigning right now to make it cheaper and easier to manufacture, by using materials that are low-cost enough and readily available in India.”

Each team member emphasized the importance of taking a holistic approach to solving design and engineering problems, and how this experience has influenced the trajectory of their careers post-graduation.

“I started off at MIT with the goal of getting as much experience as I can, so that’s why I’m doing mechanical engineering, software, and electronics,” said Nisal. “But getting into the social impact scope of how to find manufacturers and learn ‘What’s the user like? What’s the supply chain?’, has given me a lot of respect for startups, NGOs, and companies that do these sorts of projects.”

“This has pushed me further into understanding why social impact is important to me and understanding how I can find a niche intersection between that and tech in my future career,” said Smita. “It definitely shaped the reason why I wanted to do international development as a minor, helped me see the people that are affected by problems that I feel like we can solve, and has shaped me wanting to pursue public health and public policy.”

“I’ve also had a lot of interest in art, so I’ve always tried to look at things holistically and look at things from a different lens. Working on TILT has just further added to that fire,” explained Jessica. “I always wanted to go into medical technology and work on things that will directly help people, and I’ve decided to actually get a Master’s as my next step. Part of being able to design holistically is also having an interdisciplinary understanding, and working with different kinds of people, and being in different environments and cultures. Every international experience I’ve had at MIT has been an incredible growth experience.”

The TILT team is extremely grateful for the advising and funding they have received through MIT Sandbox, Rebecca Roseme-Obounou and the team at MIT IDEAS, and the MIT Legatum Center. They would like to thank the many people who have shared their experiences and advice with the team and the extended mentorship of Libby Hsu, Jack Whipple, Joe Wight, Professor PVM Rao and the Assistech Lab, Sorin Grama, Jerome Arul, and the original class team.