Developing a preliminary plan for the design of a post-war water supply and treatment system in Ukraine that engages and meets the needs of Ukrainian stakeholders, takes account of the water supply options and geological resources of the region, is decentralized and relies on renewable energy and provides citizens safe, on-site drinking water that meets either WHO Sustainable Development Goal #6 and/or EU standards.

MIT D-Lab class

D-Lab: Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene (WASH)

Community partners

- Iryna Davydova is a Ukrainian from Kharkiv currently living in the Netherlands. She has helped us gather information on the current situation of water and sanitation in Ukraine and has connected us to other Ukrainians. She has a background in water and sanitation.

- Svitlana Krasynska is the manager of the MIT-Ukraine program. She has connected us to other Ukrainians and gives input on our project as well.

- Roman Bezhenar is a water expert specializing in mathematical modeling of the radioactive compounds in the water supply due to the Chernobyl and Fukushima nuclear disasters. He is a research scientist at an Institute outside of Kviv.

- Boris Faybishenko is a senior scientist at the Lawrence Berkeley National Lab and U.C. Berkeley. He has studied the impact of munitions on water quality in Ukraine. Also, he has studied climate change in Europe and the effects of climate change on Ukraine. And, he has also researched the spread of radioactive compounds since due to Chernobyl.

Location

Ukraine

Student team

MIT students unless otherwise noted.

- Alyssa Sennef ‘24 (Wellesley): Alyssa Sennef is a junior at Wellesley College studying Biology and Middle Eastern Studies.

- Janka Hamori ‘25: Janka Hamori is an MIT sophomore studying Computer Science and Economics.

- Lai Wa Chu ‘24: Lai Wa Chu is an MIT junior in Environmental Engineering and Urban Planning.

Project context

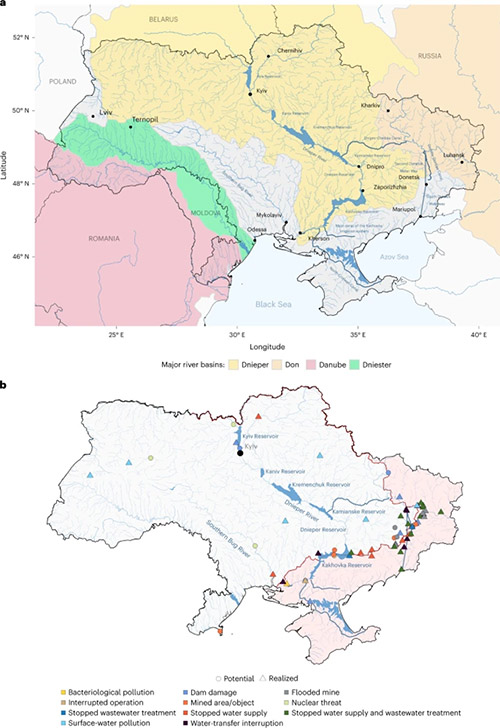

This project focuses on creating a plan for post-war Ukraine’s drinking water supply infrastructure. Ukraine currently has a highly centralized water supply system as a legacy of Soviet-era planning. This has made the infrastructure not only difficult to maintain but also vulnerable to Russian attacks. According to the National Report on the Quality of Drinking Water (2022), the length of the centralized water supply systems in Ukraine was 122,000 kilometers, of which 38.2 percent were worn out or damaged. Their wear and tear is the cause of the contamination of tap water and its non-compliance with drinking water supply standards, as well as outbreaks of diseases in Ukraine (i.e., acute nitrate poisoning in children, water-nitrate methemoglobinemia, hepatitis A, and acute intestinal infections). The escalation of the Russia-Ukraine War after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022 has resulted in over $100 billion in damage in Ukraine’s water and energy infrastructure (Kulish, 2023). According to a news report, “After the partial destruction and deliberate opening by the Russians of the locks of the Kakhovskaya hydroelectric power station, we lose thousands of cubic meters of water every day. Because of this, 70% of the settlements that receive water from the Dnieper may be left without access to drinking water” (Zharikova 2023).

Scope of work

The team will begin with identifying the potential water sources, treatment methods, and energy sources in three cities: Kyiv, Kharkiv, and Khmelnytskyi. After that, the team will work to develop a preliminary plan for Kyiv, Kharkiv, and Khmelnytsky that considers the stakeholders and hydro-geological features of the cities and addresses the needs of Ukrainian citizens. The outcome of this project will provide valuable insights and recommendations for future students and other stakeholders working on the project to redesign and rebuild the drinking water infrastructure in Ukraine, based on our three main focus areas: water resources, water treatment options, and decentralized and renewable energy options.

Project objectives

- To understand the current state of the drinking water supply infrastructure and demand in Ukraine

- To design a water supply infrastructure plan (including the water sources, water treatment methods, and energy sources) for three cities: Kyiv, Kharkiv, and Khmelnytskyi that meets WHO Sustainable Development Goal #6 and/or EU water standards and is a decentralized system 100% powered by renewable energy

- To gather input from water supply engineers and Ukrainians

References

- Kulish, H. (2023). The total amount of damage caused to Ukraine’s infrastructure due to the war has increased to almost $138 billion. Kyiv School of Economics. https://kse.ua/about-the-school/news/the-total-amount-of-damage-caused-to-ukraine-s-infrastructure-due-to-the-war-has-increased-to-almost-138-billion/

- National Report on the Quality of Drinking Water. (2022). Ministry of Development of Communities and Territories of Ukraine. https://www.minregion.gov.ua/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/naczionalna-dopovid-pro-yakist-pytnoyi-vody-ta-stan-pytnogo-vodopostachannya-v-ukrayini-u-2021-roczi.pdf

- Zharikova, A. (2023, February 14). After attacks on the power system, the occupiers want to deprive Ukrainians of water - Shmyhal. Ukrainska Pravda. https://www.epravda.com.ua/news/2023/02/14/697046/

Contact

Susan Murcott, Instructor, D-Lab: WASH

Lai Wa Chu, Student team member

Alyssa Sennef, Student team member

Janka Hamori, Student team member

![More than 30 from MIT [including a D-Lab: WASH alumna and D-Lab Scale-Ups Fellow] named to Forbes 30 Under 30 lists](/sites/default/files/2018-12/Forbes%2030%20under%2030_0.jpg)