"This gave me hope again, I believe I can make things and solve problems,” said a 17 year-old Afghani boy after completing the MIT D-Lab Creative Capacity Building training in Athens, Greece at the beginning of August.

For the last two years, we have been telling anyone who will listen (and some who don’t) that design training would be a powerful transformation tool for refugees, but our experience this August, leading a design training with a group of underage refugees in Athens, proved more powerful than we had imagined. A team of six D-Lab staff members and students led a week-long Creative Capacity Building (CCB) workshop from August 3-9th for a group of unaccompanied refugee minors. Having left their countries because of armed conflict, they are now alone in Greece without parents, several are orphaned, and they face huge challenges seeking asylum in Europe. And although we originally thought that income generation would be our major impact, we learned that the most important impact was that they could recover an identity that moved beyond that of refugee, they could see themselves in a new way: as makers and innovators.

Martha: There are 2,300 unaccompanied refugee minors in Greece, almost all boys between the ages of 12 and 17, from Afghanistan, Pakistan, Syria, Iraq, Iran, and Eritrea. They are stranded and alone in Greece with no real solution to their limbo, caught up in the often inexplicably cruel bureaucratic gears of asylum and immigration policy. Most joined the massive refugee push into Europe in 2015 and 2016, but when the borders closed, they ended up trapped in a situation that didn’t have clear pathways for the future they had hoped for. As minors, they can apply for family reunification if they have family members in other countries in Europe and many have done so. However, the bureaucracy in both the host country of Greece and the receiving countries in other parts of Europe can take over two years and the teens remain in limbo. If the youth turns 18 during that time, he is no longer a minor and is no longer eligible to join his family.

Until the fall of 2016, these boys passed under the radar of the humanitarian organizations, they lived on the streets in Athens and other cities, doing what they could to get by, suffering all kinds of exploitation. Now there are shelters for about 1,300 of them but the rest are still living in dubious, often unsafe circumstances. Finding a solution for 2,300 teens who are unaccompanied minors should be possible, we are not talking about tens of thousands but still there is no solution on the table for them. Most cannot go back to where they came from and now they cannot go forward on their journey. This leaves these boys in limbo, biding time in Greece, some waiting for family reunification, others just waiting hopefully for some solution to their situation.

Beyond the statistics of refugees in Greece, each of these boys has a story of trauma and resilience, but those stories get lost in the morass of international immigration and resettlement bureaucracy. When others see you primarily as a refugee, you are not seen as an individual, particularly one progressing towards a future. Being seen as part of a “vulnerable population” is even more disempowering. The CCB workshop changed that for these youth. It created a space where these smart, motivated young men could be just that: intelligent people learning useful skills, not refugees, not traumatized youth but smart kids with a lot of potential.

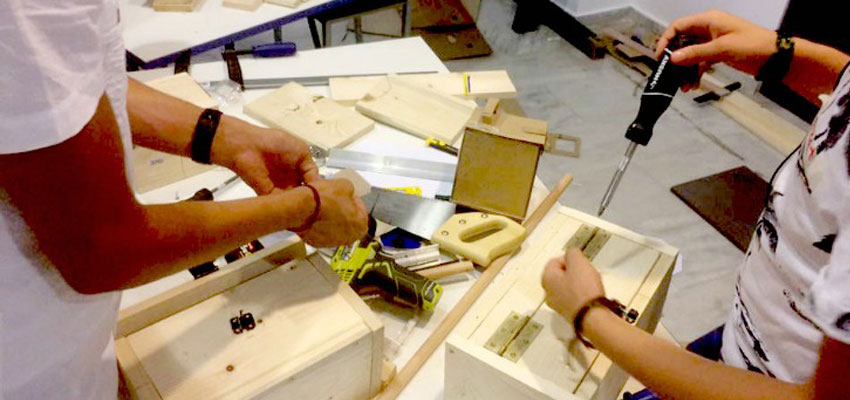

Amy: A group of 14 teens came from different shelters and camps in and around Athens, traveling for up to an hour and a half in the intense August heat to get to the training site. They spent the first three days learning the design process and gaining hands-on skills through a variety of projects and activities and during the second three days, applied the process to a project of their own choice. Their first project was to build a hand-held hot wire foam cutter which taught some basic woodworking, metal working and electronics. They used the cutter to make patterns which they then learned how to cast in aluminum at the small foundry we cobbled together in the sub-basement. The next project was originally going to be a tool box that they could put their tools and projects in. We had thought that it might be nice for them to be able to lock it, as few of them have a way to secure their belongings. As we were working with the youth, we realized that we wanted to give them more control over what they created, so we made it more open—they could design any kind of locking box that they wanted. Each one of them was given two pieces of wood, a meter-long piece of 1” x 6” and a meter-long piece of 1” x 4”. They were given hinges, hasps and a lock, and the rest was up to them. Because their supply of wood was limited, we encouraged them to make cardboard models of the box before starting. Then we taught them the basics of sawing, drilling, and fastening and they got to work making the real thing.

The variety of boxes was incredible. Every one was unique and contained a little of the heart and soul of its maker. One of the youth made a box that was a replica of a box that his grandmother used to keep treats in for him when he came to visit. Another took advantage of a knot hole in the wood, and had a charging port for his cell phone. One of the youth who loved to work on science projects built a box for his electronics tools, and designed it so that when you slid open the doors, two small LEDs turned on and lit up the inside. Another took on the challenge of making a triangular box, without the benefit of a miter box to make the angled cuts. It was a real testament to his perseverance that he finished his box without reverting to the classic rectangular shape. As they painted their boxes, even more of themselves came to the surface; one of the younger boys painted the mountains of home and the name of his little brother on his box. Others displayed their pride in and love of their home countries by painting Afghani or Syrian flags. Some looked to the future by painting the flags of countries they wanted to go to. It was amazing how such a simple activity could lead to such a wealth of self-expression.

For the second part of the training, the youth had a chance to choose their own design projects to work on. Some chose things that would be useful in the camp, solar-powered fans and a solar-powered water cooler. Another group chose to address a problem their family faced at home, building a model for a solar-powered irrigation system that could store and release water to irrigate terraces of fruit trees on the hillsides of Afghanistan. They worked in teams of three or four, alongside one of the D-Lab facilitators. Martha and I were joined by three wonderful D-Lab students (Molly and Zoe from the Humanitarian Innovation class, and Jana from the Design class) and our amazing translator, Asif, who is one of D-Lab’s financial administrators for his “day job”. The youth made friends across language barriers, taught each other what they knew, and built upon each other’s ideas to improve their designs. They drew from the skills that they learned during the first part of the week, and gained a lot of new skills. They came early every day and left late every afternoon and made sure to clean the work space and leave it spotless and organized. They expanded into a space where they could prove what they were capable of. Waiting to move on to permanent settlement or for asylum, they feel their lives are being frittered away and they are falling farther and farther behind. This design workshop reversed that feeling; they felt that they were moving ahead.

Martha: When we started planning this CCB workshop, one goal was to provide the youth with skills to invent and make things that they could eventually sell so that they could earn income. Another goal was to improve their self-esteem and help them realize their creative potential. What the youth taught us was just how important that second goal was for their own development. They are hungry for knowledge and new skills to improve their lives and are deeply motivated to learn and demonstrate what they are capable of doing. They so badly want an opportunity to grow.

Amy: The final showcase was a highlight of the week, a moment of great energy and enthusiasm, but it was critical that the youth understood they could continue working on their designs, learn new skills and make more useful things after the training was over and that this feeling of achievement was not transitory. We are pleased that Zoe, a recnt D-Lab graduate and one of the design facilitators for the workshop, has volunteered to stay on for the next three months in Athens to provide design mentoring for the youth and to run additional classes in science, technology, innovation and engineering. D-Lab is working with two partners in Athens to facilitate Zoe’s work, Faros, a Greek NGO that works with unaccompanied minors and does outreach across different networks to engage youth in educational activities and The Cube Athens, a collaborative workspace and start-up incubator that has a maker space that let us use their building for the training, Both organizations have welcomed Zoe to use their space for on-going work and encourage the youth to continue using their resources, and even to bring along their friends. The Cube will host a mini-maker fair in Athens in October where the youth can present their refined prototypes and any other projects that they have developed.

We have exciting visions for collaborating with these partners to build upon this work and open a vocational training and innovation center in Athens. Our hope is to open the center to local youth from Athens as well the unaccompanied minors and other refugees in order to give the groups a chance to get to know each other and integrate with each other. We would love to bring more D-Lab students there to do other design trainings, and hope to incorporate this into our Humanitarian Innovation class next spring. In addition, we are in discussions with another group to develop a mobile workshop to do CCB trainings in other camps in Greece. Although our resources are still scarce, we know that we need to continue to move this work forward. These smart, motivated, committed young men are getting air-brushed out of the picture of refugees in Europe and left to languish. They deserve better. We must keep faith with them, and help create opportunities for them to become who they dream of being … and it is a lot more than just a refugee.