When I started at MIT D-Lab seven years ago, I was charged with figuring out a way to measure the outcomes of D-Lab’s inclusive innovation programs. D-Lab wanted to understand the impact that participatory design programs were having on the world, and we wanted to use the tools of monitoring, evaluation, and learning (MEL) to do so.

This was easier said than done.

In the global development sector, MEL has a reputation of being square, clunky, and top-down. Many people’s first exposure to MEL is in the form of required reporting to donors, often on a phalanx of prescribed, standardized metrics that focus on numerical outputs: How many widgets were produced? How many (millions of) users did they reach?

But design is not linear. In fact, people who try to depict the design process often use circles, spirals, and squiggles. Unexpected outcomes abound: you never know what kind of creative solution (or connection, or transformation) will emerge from a design process.

At times, the two seemed irreconcilable. It became clear that simply overlaying rigid, boxy measurement frameworks onto the twisty-turny pathways of design would not work. In other words, we could not just fit a “square” framework onto a “round” process.

We began to modify MEL tools to better fit our participatory design programs, taking into account the impacts of both the product and the process of design and drawing on a more flexible and adaptive set of evaluation tools. Little by little, MEL stopped feeling like an imposed add-on to our programs, and it started feeling like a more natural and integrated part of our work. We began to ask ourselves how might we embed MEL – and particularly, the theory of change framework – as part of the participatory design process itself.

What is a theory of change?

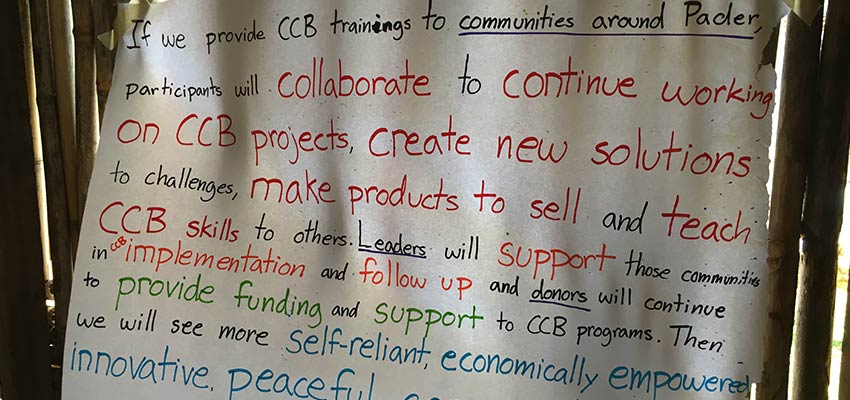

A theory of change is an explanation of how your initiative will lead to its intended impact. Written out in words, it reads like a causal statement: “If we ____, then ____ will result.” It’s often divided into four parts: inputs (your initiative), outputs (who the initiative reaches), outcomes (what those people experience or do), and impacts (how those actions affect the broader community).

A theory of change is a map for evaluation professionals; it helps us decide exactly which metrics track at which stages of a program. But it’s also a powerful design tool. It helps a team arrive at a shared vision about how the initiative actually works and what it’s aiming to do. It also helps them anticipate things that might go wrong: when you spell out a program’s logic, it’s easy to think through – and design for – the assumptions that prop it up and the ways it might fail. Just like other design tools like mapping stakeholders, creating personas, and storyboarding, a theory of change can uncover new insights and advance an idea to the next stage.

And just like design, a theory of change can be iterative. It can evolve as your initiative evolves and as you learn more about how it works. When should you develop a theory of change? At the beginning, when you’re first designing your initiative. And then, over and over again.

Why develop a theory of change in a participatory way?

If we aim to design products and services to better meet the needs of people facing the challenges of poverty, we should also measure the outcomes that are most meaningful to them.

In fact, the framework from the Impact Management Project urges MEL practitioners to ask not just “What outcome is this initiative contributing to?” but also “How important is this outcome to the affected stakeholders?”

At D-Lab, we aim to prioritize the outcomes that are most valuable to program participants and staff, and that means creating a theory of change that centers their voices.

Read on to learn about three strategies we’ve tried to incorporate stakeholder voice into our theories of change, and therefore into the outcomes that we measure and design for.

1. Run a theory of change workshop.

Over the course of a well-facilitated workshop, ranging from a few hours to a few days, program stakeholders can come together and co-create a theory of change. By the end of the workshop, the team will have a working theory of change that represents the outcomes that they all value and strive to achieve. Just like in participatory design processes, a participatory theory of change workshop can build capacity and community, and going through this exercise together can sharpen and solidify a team’s focus on its mission.

D-Lab used this method when we co-created theories of change for Creative Capacity Building programs in Tanzania, Ghana, and Uganda. In each setting, we invited a variety of stakeholders to participate in a one to two day workshop to generate a theory of change. We facilitated a series of activities, from ideation to storytelling to gathering feedback, and over the course of the process produced a site-specific theory of change for each program. Our process is described in detail in our new publication with the D-Lab Local Innovation research group, Unearthing a Theory of Change for Creative Capacity Building.

2. Interview individual stakeholders to gather the building blocks of your theory of change.

If it’s impractical to bring all of your stakeholders together in one room for an extended workshop, you can try an asynchronous option: a series of interviews. You can gather multiple perspectives on an initiative’s theory of change by asking each individual a version of the following questions:

• Who is this initiative trying to reach? (outputs)

• What do you hope they will experience or take away? What do you hope they do next? (outcomes)

• How do you hope the broader community will change as a result? (impacts)

Afterwards, you can cluster and consolidate the responses to each question to create a draft theory of change, and then invite feedback to refine it further.

We tried this with the Practical Impact Alliance Co-Design Summit in 2017, which was implemented by D-Lab in partnership with World Vision Colombia and Diversa (then called C-Innova). Each member of the organizing team shared their thoughts individually, and we consolidated them. This process was an important step to understand which outcomes were most important to each organization, to illuminate where there were differences, and to align on a shared vision at the outset.

3. Use program data to continually refine your theory of change.

In addition to developing a theory of change collaboratively at the beginning of a program, you can bring diverse voices into the process of refining your theory of change over time. The monitoring data you collect regularly from participants or users can inform you of their goals, aspirations, and priorities as well as the outcomes that they experience and value.

In your surveys, you can incorporate open-ended questions like the following:

- What motivated you to [purchase this product / sign up for this training]?

- What do you most value about the [product / service]?

- What was the most important change you experienced as a result of the [product / training]?

Open-ended questions like this let you go beyond the prescribed list of outcomes you’ve already committed to measuring and instead allow your users to surprise you. If you monitor these questions for patterns over time, you can see how they do or do not align with the original theory of change driving your program.

We did this to build a theory of change for International Development Design Summits run through the International Development Innovation Network program. Over five years and 12 design summits, we collected pre-summit, post-summit, and follow-up survey data from all participants. In the pre-survey, we asked about participants’ short-term and long-term goals, and in the follow-up surveys, we asked them to reflect on the value of the summit and the changes they had experienced in the intervening time.

Over time, these questions challenged our thinking. Our original theory of change for the program had focused on how summits might inspire and enable participants to continue designing solutions to community challenges. But through these surveys, we kept hearing that participants were motivated to carry the co-design methodology forward and teach it to others. This was happening often enough that we updated our theory of change to include these new initiatives to teach co-design. We began to measure it explicitly and to design new initiatives to support it.

---

In the last seven years, the theory of change has become a central tool in D-Lab’s work: we include it as a module in our online course on participatory design, we teach it to the students in three of our MIT classes, and we use it to frame the work of our three pillars. And because of it, we are able to collect data that enriches and informs each new trip around the design cycle, whether for a product, a class, or for D-Lab itself. When we get it right, the data we collect is the data that matters most to the people closest to the work.

D-Lab has always challenged the way development innovation works, asking, “Who decides what gets designed?” and “Who gets to be a designer?” Now, we’ve added to that list, “Who decides what gets measured?” May we keep asking that question, pushing ourselves and the sector to set our sights on the goals that are most meaningful to the people at the center of the work.

About the Author

Laura Budzyna is the Monitoring, Evaluation and Learning Manager for MIT D-Lab is the Associate Director for Innovation Practice. She leads the visioning and development of D-Lab’s impact measurement strategy, implemented evaluations on more than 20 inclusive innovation programs, and advises some collaborating organizations on their impact measurement strategies. She is a global development practitioner and evaluator committed to participatory, flexible, and learning-focused measurement and management for the social impact sector. She holds an MPA in Development Practice from Columbia University’s School for International and Public Affairs. She is the author of The Metrics Café, a framework that aims to bridge the divide between funders’ and grantees’ impact management needs.

Related Publications

Unearthing a Theory of Change for Creative Capacity Building

The Metrics Café: A Guide to Bring Funders and Grantees to the Table