My daily work as a family doctor can at times feel distant from my prior work as a D-Lab engineering student. It’s been a long time since I designed a device or did a calculation more complicated than simple arithmetic. However, I do feel there are some day-to-day connections: the ability to work directly with people to solve problems and the fact that technical knowledge is usually only a small piece of what is needed; human skills such as humility, openness, and teamwork are often much more important. And sometimes, when I am really lucky, I get a chance to bring my engineering and medical worlds together much more directly, as in my recent work on water and health in Peru.

Santa Clotilde, a remote town accessible only by boat on the Napo River in the rainforest of Peru, is home to the region’s only small rural hospital. There is a significant burden of waterborne disease in the area, including parasites such as giardia and roundworm that cause diarrhea, malnutrition, anemia, and occasionally death. When I traveled to Santa Clotilde to work as a physician in the hospital for the month of June, I wanted to bring water-testing supplies for the public health staff to assist in their efforts to reduce waterborne disease.

However, as the town of Santa Clotilde only has electricity for five hours per day and the samples must incubate for 24 hours, an electric incubator was not an option, so I put in a call to D-Lab to inquire if I might get access to the materials needed for a phase-change incubator. The phase change incubator is a low-cost, low-maintenance incubator to help test for microorganisms in water supplies developed by D-Lab founder Amy Smith when she was a graduate student..

I had first used a phase-change incubator ten years ago, during the summer of 2006. A freshman at MIT at the time, I had teamed up with another MIT student, Froylan Sifuentes (Chemical Engineering ’09) to spend our summer working with a small community in the Ecuadoran Amazon Rainforest called Santa Ana to improve their access to safe water. We had the generous financial support of an MIT Public Service Center Fellowship and mentorship from both D-Lab and the Environmental Engineering faculty. The most important tool we brought with us was the “Test Water Cheap” system developed by Amy Smith and D-Lab, which uses disposable baby bottle liners, which are sterile, and a syringe to pass water through a fine paper filter, which is then placed in a culture medium and incubated for 24 hours in a phase change incubator. The next day, tiny blue and red dots appear, each one representing an E. coli or other coliform bacteria, respectively. Count them up and you can quantify the level of fecal contamination and therefore disease risk in that water source. I will never forget the look on the faces of the women in Santa Ana when they were able to actually see and hold the bacteria they had always been told was in their water, making their children sick, and compare it to the clear sky-blue sample of boiled or chlorinated water.

Ten years later, I brought another phase-change incubator to the rain forest, this time to the Peruvian side of the same greater Amazon river basin, to Santa Clotilde. I wanted to empower the local public health staff to bring that same sense of awe and understanding to their local community members as a tool in their efforts to reduce water born disease in the area. The information from the tests is invaluable – sometimes a water source that appears to be clean can have hundreds of times more contamination than another source the looks much dirtier.

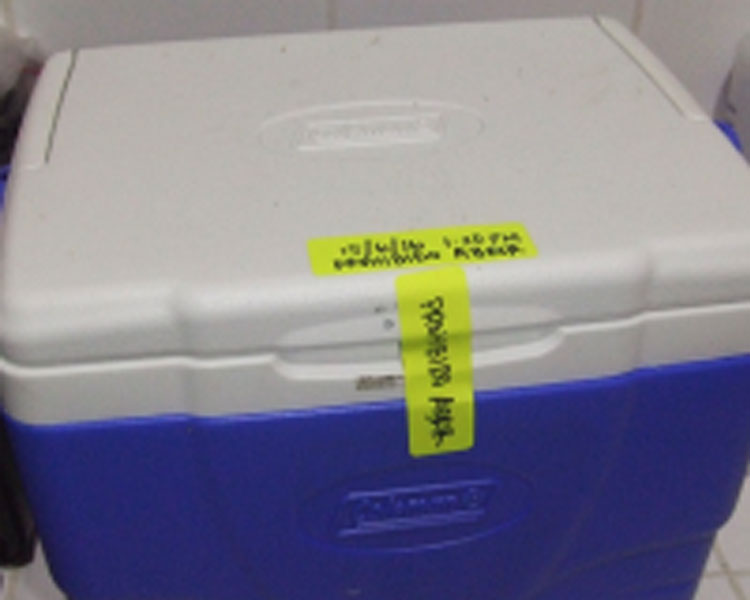

To me, the phase-change incubator really exemplifies the essence of D-Lab. It takes on an important problem in the developing world: how to incubate specimens without electricity, keeps the cost low compared to an electric incubator, and uses clever science and engineering to solve the problem. In this case, the incubator takes advantage of something we all learned in high school chemistry. Remember the plateau on those phase change diagrams? A material maintains the same temperature throughout the time it is changing phase, and the D-Lab team found a wax that melts at human body temperature and sealed it in plastic packets. Melt the packets of wax in boiling water until they are almost but not quite all liquid, place them in an ordinary portable cooler, close the lid, and 24 hours later the wax now mostly solid but still partially liquid so the contents are at essentially the same temperature. Simple, cheap, and brilliant.

The public health staff at Santa Clotilde rapidly learned the technique and are using it to develop infrastructure improvement and educational programs. The lab staff at the hospital were also intrigued about the idea of using an incubator like this for other sorts of cultures, such as blood cultures, to guide treating patients. As I look into my future as a physician caring for patients in remote areas of the world, I have renewed appreciation for my roots at D-Lab and as an engineer and am excited by the possibilities of appropriate technology for improvement of public health and health care in developing countries.