The Art and Science of Qualitative Data Collection

What is impact? According to the experts at the Impact Management Project, impact can be broken down into five dimensions: what, who, how much, contribution and risk. As an MIT D-Lab Monitoring, Evaluation, and Learning Fellow working with D-Lab Scale-Ups Fellowship venture Kwangu Kwako, Ltd. (KKL), this summer marked an opportunity to dive deeper into the question of impact along these five dimensions. Particularly, the organization wanted to know how moving to upgraded housing affects tenants in other areas of their lives. Through a series of face-to-face interviews with KKL’s customers and beneficiaries, I have begun to shed light on this difficult question.

The United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, and the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights all recognize the importance of access to adequate housing. Research indicates that substandard housing affects its residents’ health and education outcomes as well as their quality of life. KKL offers a cost-effective pathway to achieve better housing for all. But to what extent was KKL’s intervention delivering on these outcomes?

As collecting experimental data on these sectors can be quite challenging and expensive, our survey endeavored to gather information that would give us an idea of whether we were heading in the right direction, instead. We leaned heavily on self-reported data on poverty probability, global self-worth, customer satisfaction, social inclusion, and health, and sought to identify before and after trends.

One lesson I have learned through this process is that the process of data collection is an art as well as a science. Even the perfect survey (and if it exists, it is not the one that I made) can be derailed by unpredictable interpersonal dynamics. Who would have thought that recording video footage could possibly bias people’s responses? (Turns out, everyone but me.)

Another takeaway for me was that format matters. I had designed the survey using Google Forms, knowing that they would be administered orally. I did not account for the nuances that would be lost in translation in this process, however. The visual component of written questions, such as a 1-10 scale or a five point Likert scale, does not convey orally nearly as well as it does on paper or on a screen. In response, since there is not much practical value in distinguishing “Disagree” from “Strongly Disagree,” for instance, we simplified these response choices to remove the extremes on both ends.

Once we replaced me with more competent enumerators, Winnie and Milka, our data collection sped up and smoothed out considerably. We removed the power dynamics of gender and nationality and facilitated a more direct process via native Swahili speakers.

At the end of a summer full of “no duh” moments such as these, what have we learned and what can we say about the impact of KKL?

Stories from the Field

During my first stakeholder meeting with KKL, I had the opportunity to meet Milka Achieng, a charismatic young woman who has grown up in Kibera’s often-volatile Gatwekera neighborhood. Milka had worked with KKL on data collection in the past and would be helping me on this round of interviews as well.

Milka shared her experience living and working in Africa’s most infamous settlement, from the dynamics of power and justice to land ownership and education. While her community is unquestionably under-resourced, Milka received a free education up until secondary school via an NGO-operated program promoting girls’ education.

“It’s always girls,” she confided to me with a look, which I had trouble discerning between sheepishness and confusion, “There is nothing for the boys.” Now Milka works for a community-based organization named Diptop, which offers microloans as well as a leasing structure for motorcycles.

While Milka’s strong education, steady employment, and secure land tenure inherited from her father put her far ahead of many of her neighbors, she dreams of a better future for her and her young daughter, a future that she hopes will include a KKL house. When I asked to her about her interest in a KKL house, she said, “It is always about fire. In Kibera we fear fire and the security.”

Throughout my time in Nairobi, I was grateful to have Milka’s wit, warmth, and capability guiding me physically and socially as I blundered my way around the city asking questions.

Collecting data from current tenants was one of my top priorities for my field interviews, and Milka quickly introduced me to Maxwell, the Diptop employee currently living in the organization’s KKL structure. Before KKL came to Kibera, Maxwell lived on the same plot where he currently resides, although in a wholly different situation.

“The house where I lived before, it was a muddy house, not stable. It was dirty. It was not comfortable. I would fear to welcome a visitor in. It was very untidy. In the place where I used to stay you can't even find somewhere to put your files because it's a muddy house. You can get your file maybe stole by a rat. You are very dirty. It was not comfortable,” he explained to me, clearly nervous of the camera that I had unceremoniously foisted in his face.

Most hilariously, when I asked him about the most significant change he had experienced since moving in, Maxwell connected some dots that I would be hesitant to include on our impact page:

“The biggest changes that I saw, I came in and I got married because now I can let someone inside. So now, I have a child. Before, I didn't feel comfortable because in a dirt house, I can't imagine even to have a girl visit me. I can ask some friends outside there to assist me to welcome my visitors. Now here even my friends, they just admire this house. They just want to bring their visitors to visit here to pretend that this is their house.”

While we are happy for Max here at KKL, we are still hesitant about promising the wife and baby sales package on our website.

Although talking to our beneficiaries was important, it was equally key for me to gather feedback from our primary customers, the structure owners. KKL’s other primary presence in Nairobi is in the Kawangware settlement (featured in this UNICEF video) where I spoke to two structure owners, George Mburu and his aunt, Monica.

Despite some loan-related anxiety, I could tell from speaking with George that he was satisfied with structures especially compared to his previous ownership experience:

“Many of the houses before were vacant and not in good condition. With the others, now you can see they are all full. Sometimes people shift, but we can't stay for long with them remaining vacant. At least they are in demand. It's not like what we had before with mabati houses. Before Kwangu Kwako I could not afford to build good houses when people can come and be comfortable. I think everything with Kwangu Kwako--it's a life change.”

He also went on to mention the birth of his second daughter, pictured above, since working with KKL, so perhaps we should revisit advertising the wife and child package on our website after all!

What Do the Data Say?

In addition to delving into the rich experience of our customers and beneficiaries, our surveys unearthed several trends. We interviewed three current structure owners and ten current tenants across our Kibera and Kawangware sites, representing 100% and 66% of our respective client bases.

While we strived for consistency across sampling, initial language barriers and early versions of our survey questions may have contributed to some confusion among respondents. We had particular difficulty conveying the meaning of questions pertaining to global self-worth. However, elaboration from our enumerators translated these questions successfully. It was also particularly challenging to find an appropriate time to administer surveys, as many residents were absent during regular business hours and on weekends were reluctant to step away from time with friends and family to engage us. Our enumerators worked around this challenge with admirable persistence and charm.

A common concern in slum-upgrading programs is the potential deleterious secondary effects such as gentrification and displacement. This phenomenon has been observed in other Nairobi projects wherein low-income residents were granted upgraded housing, which they promptly rented out to middle-class Kenyans while resuming residency in their settlement housing.

It is thus reassuring to note that 89% of residents in our structures moved from mabati (iron sheet) houses from within the same communities where they currently live (the other 11% of respondents did not specify their previous living situation). There is no middle-class replacement gentrification effect demonstrated by the data.

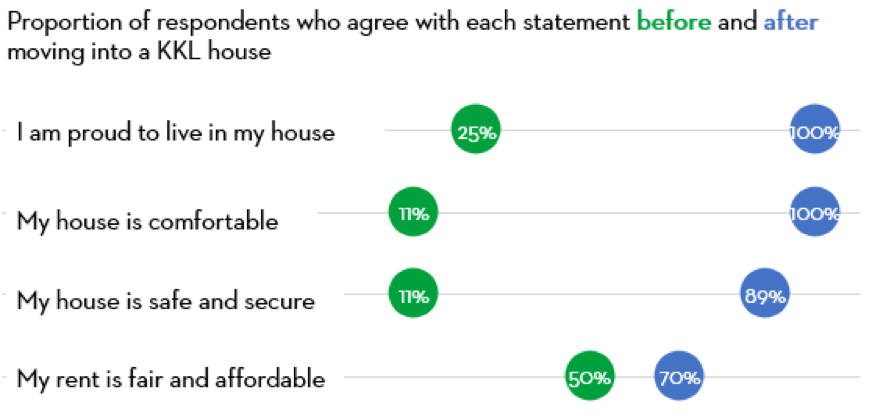

When characterizing their before and after experiences with KKL, tenants reported improvements in comfort, security, and pride:

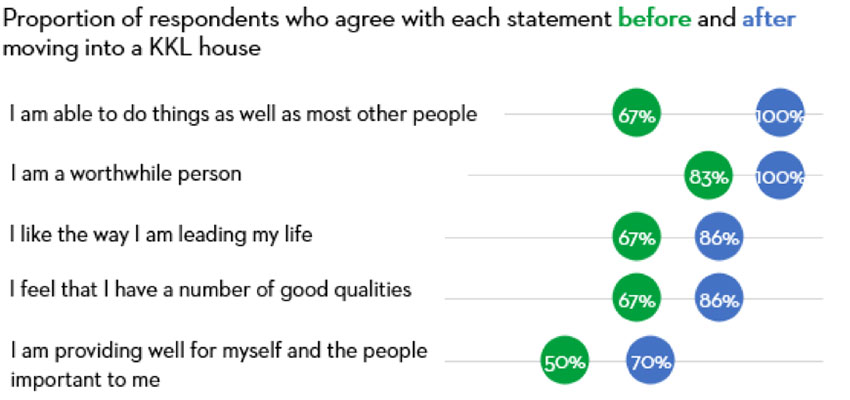

Tenants also reported slight improvements in global self-worth since moving into their KKL structures:

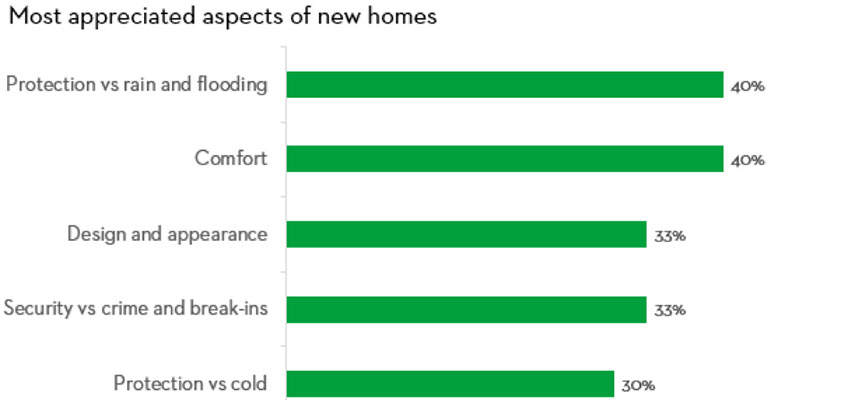

Sixty-six percent of tenants also reported an increase in the number of times they hosted guests in their homes. Finally, when asked what they appreciate most about their new homes, tenants emphasized protection from the elements, appearance, and security:

While customers and beneficiaries express high levels of satisfaction, two outstanding issues cropped up repeatedly from the data. Among structure owners, the terms of the loans proved problematic, as the payments more or less were the same as the rent prices they were collecting, resulting in zero or net losses on the homes. KKL is currently exploring alternative financing measures to address this issue.

Finally, among tenants, the primary critique of the structures appeared to be the temperature within the houses on the hottest days of the year. In testing, KKL houses measured 5 degrees cooler than traditional metal shacks; however, the overheating is clearly still an issue. KKL take customer feedback seriously and are already working on a solution to improve this.

What Next?

With my time at KKL ending this week, I am happy to report that the company stands in very solid position regarding customer satisfaction. Although I have tried, it is difficult to convey through words, pictures, numbers, and figures just how dramatically this product can change someone’s life. To understand the difference, you probably have to experience it for yourself.

For KKL, this data will soon be displayed on an “Our Impact” page of the KKL website, which is currently under construction. This month, Winnie will also depart for the US where she will take our story to investors at the Global Social Benefit Institute (GSBI) in Santa Clara, CA. We know she will do a great job!

For me, I will return to the United States and resume my studies at Fletcher, taking along the lessons I have learned here about social enterprise, monitoring and evaluation, survey design, and data collection and carrying with me the stories of the people who were kind enough to welcome a stranger into their communities.

Thanks very much to Kwangu Kwako, Ltd., MIT D-Lab, Tufts Institute of Global Leadership, and Fletcher Office of Career Services for coming together to make this experience possible for me, and special thanks to Winnie Gitau and Simon Dixon of KKL and Laura Budzyna at MIT D-Lab for guiding me along this summer. Asanteni sana!

About the writer

Geoff Tam is a rising second-year master’s student at the Tufts Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy studying development economics and human security. His work with the Kwangu Kwako, Limited is sponsored by the MIT D-Lab, the Tufts Institute of Global Leadership, and the Fletcher Office of Career Services.