A team of students heads to Madagascar…

In January 2024, for MIT’s Independent Activities Period (IAP), a team of (enthusiastic) MIT and Wellesley students traveled to the rural South of Madagascar for three weeks. The trip was dedicated to testing a water vapor condensing chamber that the students designed over the course of the Fall 2023 semester in D-Lab: Development. From September through December, the team virtually collaborated with Tatirano, a social enterprise in Madagascar dedicated to providing clean drinking water and empowering women through water access. Tasked with designing a condensing chamber that would connect with Tatirano’s existing evaporation chamber (called the Pano Rano), the two chambers together would create a solar distillation-based desalination system. January was the time to put their ideas in action, with an itinerary packed with testing in the field!

Madagascar’s water insecurity and our solution

Madagascar is one of the poorest countries in the world. With a population of 28.92 million, 75% of Madagascar’s population lives in poverty. (1)The island is also facing a severe water crisis: only 34% of its population has access to safe water, and only 12.3% has access to basic sanitation services. (2) This severe and urgent situation places Madagascar at the lower end of 76 developing countries concerning sanitation access–4th worst in sanitation and 3rd in water accessibility. (3)

Marginalized groups are the most affected by Madagascar’s water crisis. In particular, women and children are held responsible for acquiring water for their households, and thus suffer the consequences of water scarcity, professionally, and socially. Moreover, the time spent on acquiring water results in detraction from education and economic opportunities. Exorbitant prices lead to some parents having to take their children out of school to be able to afford water. Increased economic involvement of women in concert with improved water sources are imperative.

As a solution to water insecurity and in hopes of addressing the disproportionate effect on women, Harry Chaplin founded Tatirano in Fort Dauphin, Madagascar. The company began with rainwater collection, and is now expanding towards desalination in order to leverage the supply of seawater and brackish water accessible to locals. The desalination is targeted towards Madagascar’s rural South; thus, the team traveled to Ambovombe (the desert!!!).

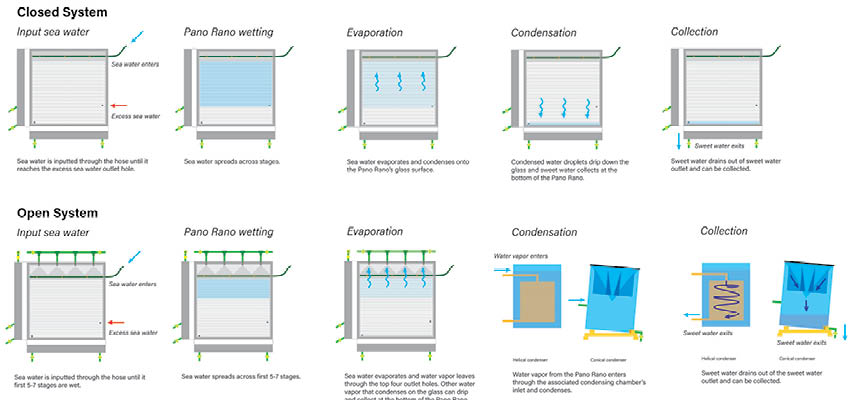

Tatirano’s existing innovation is the Pano Rano evaporation chamber, which evaporates seawater into water vapor through solar distillation. The D-Lab team aimed to create a condensing chamber that would collect the steam produced by the Pano Rano chambers and condense it into clean drinking water. Over the course of Fall 2023, the team prototyped two condensing chambers, and tested them in the D-Lab workshop.

We tested two prototype designs: (1) a conical surface exchanger with fins and (2) a helical copper coil submerged in seawater. The conical surface exchanger is a two-part design, with a bucket and a cone-shaped piece of sheet metal. The bucket is attached to the steam source, or Pano Rano. The convex side of the cone-shaped metal is the condensing surface that the incoming steam contacts. Sea water is stored in the concave volume of the cone to cool the condensing surface. This serves a dual function to simultaneously pre-heat the sea water before it’s placed into the Pano Ranos for solar distillation. As steam enters the bucket, it hits the cone-shaped metal surface and drips down to collect at the bottom of the bucket. To improve heat exchange and efficiency, fins were welded onto the convex side of the cone to increase the surface area.

The helical condenser is based on similar condensers used in chemistry and distillation applications. The evaporated water is pushed through a coil of tubing submerged in a bucket of salt water. This allows for efficient heat exchange to condense the vapor into liquid (desalinated) water.

How it works

Getting settled In

Antananarivo

The first of our MIT group members to arrive had a few days to visit Madagascar’s capital, Antananarivo, a sprawling city of 2 million residents. We headed to the Queen’s Palace, an imposing stone building sitting atop the city’s highest hill and which used to be the home of Madagascar’s royalty. We walked around the Royal complex which offered views of the city and its red tin rooftops, as well as the local soccer team’s new stadium and the lake from which the entire city’s water is drawn, both for drinking and general purpose.

The next day Dr. Angelos invited us to his home where he is running a host of projects related to sustainable energy sources and passive desalination. We met the four ESPA Master’s students that we were collaborating with to improve the original Pano Rano passive desalinator design. They showed us their prototypes and we shared our work with them before sharing a big lunch. They even took us around a Malagasy supermarket and showed us some products you could only find in the country, including World Cola drinks and jam made from pok-pok (a little round yellow berry). Dr. Angelos then took us on a special tour of the Gouty biscuit factory he worked at as a technical director for many years, and we got to see the entire process of making a butter biscuit from ingredient mixing to cooking to packaging. We left with 8 kilos of biscuits they kindly gifted us and that sustained us for the rest of the trip!

Next stop: Fort Dauphin

We stayed in Fort Dauphin – Taolagnaro in Malagasy – for a few days before heading out to Ambovombe and two days after returning from Ambovombe. Fort Dauphin is a relatively big, coastal city in the southern part of Madagascar, with an approximate population of ~70,000 people. We took a plane, which was smaller than most regular planes, to get there. Fun fact: our plane tried to land but it failed because of heavy wind, so we had to try it again (scary yet thrilling moment!). We explored the city a bit as well. We went to famous beaches in the area such as Ankoba Beach and Libanona Beach. One interesting thing about the city too is its incredible amount of Tuk-tuks, yellow, smaller-than-a-car-and-bigger-than-a-motorbike taxis. We rode them a few times and it was very fun.

Here, we also visited Tatirano’s headquarters and lab. Despite its relatively small HQ, the NGO has a huge impact in the city. Most of the people and places – restaurants, hotels, groceries shops – sell mostly Tatirano’s water. We noted how well respected it is. Close to the HQ, we visited a school which had a rainwater collecting system and a collective bathroom with composting toilets, all of them built by Tatirano! We also checked their lab, where we did most of the building and assembly of the Pano Rano’s. They have a whole facility to purify water as well as the construction team HQ. There we built and improved the design of the prototypes, aided by the construction leaders Delicia and Hervé. It was overall a very pleasant stay and we enjoyed it a lot!

Testing site: Ambovombe

Our testing took place in Ambovombe, a small small small (worth emphasizing) town about 4 hours southwest of Fort Dauphin—4 hours on the bumpiest road any of us had ever been on, only a tenth of which was actually paved. Fortunately, all six of us, plus the four ESPA students, and Harry, Karl, Skylar, and Dr. Angelos survived the journey in 4 pickup trucks. On the way there (and on the way back as well) we stopped at a market to buy local, tropical fruits like pineapples, mangos, coconut and passion fruit. This stop was a must—the fruits are exceptional. The trip was across expanses of desert and agricultural fields, with a gradual progression from lush forest to sparse shrubs and cacti.

The village did not have asphalt roads, consisting basically of a single, straight avenue connecting the whole village. At the center of it, there was an informal market where people sold everything, from clothing to raw meat/fish to sim cards. It felt like the heart of the city. Besides our excursions we describe at the end, there was not much to do there since we were testing all the time.

Testing the evaporation and condensing chambers

Upon arrival, we began by unloading all of the testing materials: four Pano Ranos (approx 250 kilos each), their stands, six sheets of glass, a generator, both condensers, and a ton of other materials and equipment. But many hands made light work! On the following day, we did a quality check and prepared all of the Pano Ranos, nailing in hoses and sealing on sheets of glass. The sun was intense our first two days, and we were ready for some good testing throughout the rest of the week.

Our testing days started at about 6:30AM and went until 5PM each day, with breakfast and lunch thrown in at random times. Days 1-3 of testing were all about learning. How much water do we input into the Pano Ranos for evaporation? At what intervals do we take measurements? How many times a day do we need to reapply sunscreen?

Across the day, we kept track of how much water was being inputted into each Pano Rano, and how much water was being condensed in the control (evaporation and condensation chamber combined) as well as the experimental groups (the two condenser prototypes). The ESPA students also tracked ambient temperature, humidity, and solar irradiance.

The week of testing was a major learning experience for us, especially deciding what variables to change day-to-day—based on weather conditions, as opposed to setting a fixed time and conditions and running the same tests over and over again in the controlled environment of the DLab workshop. How do we extract meaningful data?

Unfortunately, the first few days of testing were met with cloudy weather! This negatively impacted our results, as the Pano Ranos’ evaporation was not at full efficiency and therefore did not provide insight on realistic performance (on a typical sunny day). However, on the last two days of testing, it was finally sunny! We collected a lot of good results, especially because we had our testing methods solidified and could collect consistent results.

Additional excursions

Entrepreneurship is not exclusive to MIT Sloan. Our first excursion in Ambovombe was to a so-called “peanut factory,” where we explored the eccentric yard of a local entrepreneur, Taza. His work is to change the mindset of the people in Madagascar, so that they can take advantage of the resources they have to change their reality. He makes peanut butter, soap, wine, and a bunch of other products, all from local materials. He farms many different types of cacti, he builds wine cellars, he grows cassava on minimal water, and he builds bricks using a hydraulic press. Now, he will also be testing Tatirano’s Pano Rano technology and (hopefully?) using the water for agriculture.

While in Ambovombe, we made a quick trip out to a beach that was nearby. Or so we thought… Turned out that it actually took an hour drive and thirty minute walk in the baking sun to reach the water. But it was absolutely gorgeous, and when else would we get to hang out on the beach with a bunch of Zebu and goats?

Another memorable excursion in Ambovombe was an afternoon trip to visit Fraternidade sem Fronteiras (FSF), an NGO run by a Brazilian man named Igor, who graciously showed us around. The compound included a health clinic (the best in the area) and a small village with over 100 families, along with a school and a canteen. At-risk families had been moved there, and they worked making charcoal and weaving baskets and dolls. We chatted with the leaders there about access to water and the challenges of keeping everyone healthy.

We were lucky to get to visit FSF a second time the following day, where we dropped off all of the candy that Dr. Angelos had given us from the Gouty Factory. We walked around the compound again and got to serve lunch to the families.

We all found our experiences at FSF to be very thought-provoking, from seeing the clinic’s infrastructure, to being bombarded by hundreds of children asking “Comment tu t’appelles?” (what’s your name?), to not having enough meals to feed everyone at lunch.

Reflections and fun memories

Beyond our testing and excursions, we enjoyed getting to know Malagasy locals, learn about traditions, eat Malagasy cuisine, and understand the country’s social, economic, and political context. The ESPA students taught us one of their favorite board games, called Ludo, which we played multiple times at meals. We also taught the ESPA students card games from the US, amongst other fun games. There was a lot to learn and absorb, and many experiences that sparked our own introspection!

“This was such an eye-opening experience of living with and interacting with people who face water and food insecurity every day. We spent the semester learning about these challenges, but it’s so different actually seeing this reality firsthand.” Thiago, Class of 2025, MIT Department of Computer Science

“I could carry 6 meals with one hand, and half of the people could not even get lunch.” Mako, Class of 2026, Wellesley, reflecting on serving lunch at FSF to families in need

“Sometimes technology isn’t the answer to these types of problems—or at least, not technology in a vacuum. You need to take multiple approaches, such as social interventions, that build the trust of the community.” Sophia, Class of 2023/4, MIT Department of Mechanical Engineering & Architecture

“The role of engineers in countries like Madagascar is to work hand-in-hand with the community to develop solutions that will survive long term.” Angelita, FSF NGO

“You cannot import solutions. You support local people’s initiatives, and understand their communities.” Karl, University of British Columbia in Vancouver, Canada

“Madagascar has all of the riches, they just need to learn to take advantage of them.” Taza, Local Entrepreneur

About the MIT D-Lab team

Sophia Chen, MIT Class of 2023/4, is double majoring in Mechanical Engineering and Art/Design. Sophia plans to work in the field of global health in order to address resource inequities and gender inequality, after getting an MD/PhD. Lilly Heilshorn, MIT Class of 2025, is a Mechanical Engineering major from Pennsylvania who loves anything outdoors, especially scuba diving and sailing. Lilly wants to concentrate in Sustainable Product Design and keep traveling! Mako Irisumi, Wellesley Class of 2026, is a Computer Science major born and raised in Japan. Mako has a deep interest in the Department of Urban Studies and Planning (DUSP) courses at MIT and is passionate about using AI to improve infrastructure systems. Audrey Lorvo, MIT Class of 2025, is an Economics major also minoring in Statistics and Data Science and in International Development. Audrey grew up in Latin America, Asia and Europe which fuelled her interest in economic development and reducing inequality. Luka Srsic, MIT Class of 2025, is an Urban Planning major concentrating on Negotiations with a minor in Political Science. Luka is passionate about Virtual Reality and Policing Policy.

More information

MIT D-Lab class: D-Lab: Development

Contact

Libby Hsu, MIT D-Lab Associate Director of Academics