During the fall 2023 D-Lab: Develoment class, five students including MIT students Brandon Worrell ‘24, Nima Hyolmo ‘24, and Eileen Zhang ‘25; Ashley Yang ‘26 from Wellesley; and Hien Le ‘24 from Harvard collaborated with the Indian Institute of Technology Kharagpur to design affordable, robust weather-resilient bamboo roofs for traditional homes in order to improve the livability of bamboo houses in Eastern India’s periurban and rural areas. During MIT's Independent Activities Period (IAP) in January of 2024, Brandon, Eileen, Ashley, and Hien traveled to India with trip leader Nikita Kulkarni, an MIT master in city planning candidate, to further their work in situ. Following is their account of their work there.

January 9, 2024

On our first day at the Auroville Bamboo Center, we received an informative tour of the wonders of bamboo architecture. Such structures included our own meeting room (which was made by volunteers), a large treehouse, musical instruments, and a museum that housed intricate bamboo designs and crafts.

We then learned various bamboo techniques, including bamboo splitting, bending, and common joineries. The process of splitting bamboo involved a bamboo culm being inserted atop a metal bamboo splitter and being repeatedly thrust into the ground either through a hammer or gravity until even strips of 6 or 8, depending on the desired width of bamboo, were created.

The bamboo bending was needed for straightening purposes; this was shown with a culm around 10 feet in length. A blow torch, water basin, cloth, a stand to hold the bamboo, and at least four people were needed. The blow torch would be targeted at the nodes of the bamboo and kept on as another person would push forward to bend it either forward or backward, depending on the inflections of the bamboo. The water basin and cloth were there to cool the bamboo to set the bends in place as they worked on other nodes

The most hands-on opportunity was through the creation of the joineries. There were three we completed, but the most applicable and strongest one was the fish-mouth joinery, made with a couple of easy steps. First, we identified two bamboo culms that were similar in size and also got two rods that seemed around the circumference of the hollow area in the culms. Then, we got a circular drill and drilled two identical hemispheres on either side of one culm. We then sanded the two rods to fit snugly into the culm and did the same hemispherical drill on the other culm to fit the second rod. We then made bamboo nails out of chiseling bamboo strips and fitting them to the size of the drill bit to fit the two pieces together.

January 10, 2024

On our second day at the Auroville Bamboo Center, we shifted our attention from creating specific, separate types of bamboo joineries to actually building those joineries into a large-scale structure, i.e., a bamboo “house.”

Upon our arrival, the “skeleton” of the house had been largely set up. The remaining tasks included building a “door,” panel-casting, and covering up the roof. The panel casting would be achieved by manually weaving the bamboo strips, which will be explained in a section below. For this first day working on the house, we focused on the door.

We kickstarted the process by digging two holes to plant the main bamboo poles for the door. The poles were then reinforced by cement.

Next, in inserting the horizontal bamboo culms into the standing frame that would later serve as edgings for the panel casting, we had the opportunity to put the joineries techniques we’d learned the previous day, i.e., the fish mouth joints, into practice.

We spent the first half of the day finishing the joints. There were eight horizontal culms needed for the door, thus in total, we were working on eight joints.

For the second half of the day, a team from the Indian Institutes of Technology (IIT) team walked us through their casting techniques, where bamboo strips and wires were used to create two separate frames. Then, a layer of sikadur was applied, and coarse sand was sprinkled on top of it for the sake of friction. Finally, layers of concrete mixture were alternated between the two bamboo strip frames. We left it to dry for the following 24 hours.

January 11, 2024

On our third day at the Auroville Bamboo Center, we learned the local technique for constructing bamboo-reinforced wall slabs. Bamboo is a strong support material because its high tensile and compressive strengths are comparable to that of steel. In addition, since bamboo is a flexible material, it can be weaved together to construct the frame for the wall slab.

Before proceeding with the wall slabs, the locals taught us how to use rope made out of coconut husks to tighten the joineries of the doorway. For this joinery, bamboo is split at the end and folded over another perpendicular bamboo segment. Holding onto a loose end of the rope, the other end is tightly wrapped around the bamboo columns. The two ends are tied together, and adhesive can be added to the knot.

We used the bamboo splitter to create thinner strips of bamboo for weaving. The vertical bamboo strips are attached by drilling rectangular holes into the top and bottom bamboo segments. Then, horizontal strips are weaved through the vertical strips from the bottom up. The weaves need to be tightly packed to prevent cement mixtures from falling or cracking in the future. Furthermore, we experimented with two different kinds of cement mixtures: traditional cement and another with red mud. The presence of red mud reduces the amount of cement by substituting it with a local resource. Interestingly, we used manufactured coarse sand in both mixtures because natural sand is not locally available in Auroville. After spraying the bamboo weaves with water, both mixtures were smeared against the bamboo wall frame with a trowel and hands. Generally, we found that it was easier to work with the red mud cement mixture because it easily adhered to the bamboo weaves.

Within an hour, we finished spreading all of the cement to create two different wall slabs. A second layer of cement will be added to these wall panels, so we used a brush to create rough surfaces to enhance future binding. Now, we just needed to wait for the cement to dry.

January 12, 2024

Venturing out of the Bamboo Center, we took the day off to explore Auroville’s vibrant community and workshops. In the morning, we visited the Matrimandir, the center of Auroville, for a meditation session. The golden structure contained several meditation rooms inside as well as a large lotus fountain underneath. Throughout the orb, Auroville’s values were engraved into stones and displayed. Just a few steps away, a large Banyan Tree with aerial roots towered over the garden and amphitheater. Photography was prohibited inside of the Matrimandir, and visitors had to remain silent to preserve the tranquil environment. The entire experience was incredibly peaceful, allowing us to admire the beauty of the Matrimandir and learn about Aurovillian values.

Later in the morning, we drove to the site of the Sacred Groves, an ecological construction project for a house that was primarily built with reused demolition waste. In 2016, the Indian government mandated cities with over 100,000 people to ban demolition waste and wanted all government buildings in the future to be built with demolition waste. Auroville’s project is also part of the larger, national effort to adopt sustainable construction technologies. We also learned that in Auroville, no one owns or inherits houses. All property and buildings belong to the larger community and are transferred between people.

Next, we briefly visited the Earth Institute, which specializes in brick formation. They had several wind-powered machines to form and pack bricks together. Furthermore, as part of their research, they collected soil and rocks from all over the world.

To finish out the day, the IIT team showed us their current prototype for bamboo housing. Their design consists of bamboo culms attached to metal joints and held in place with bolts.

January 13, 2024

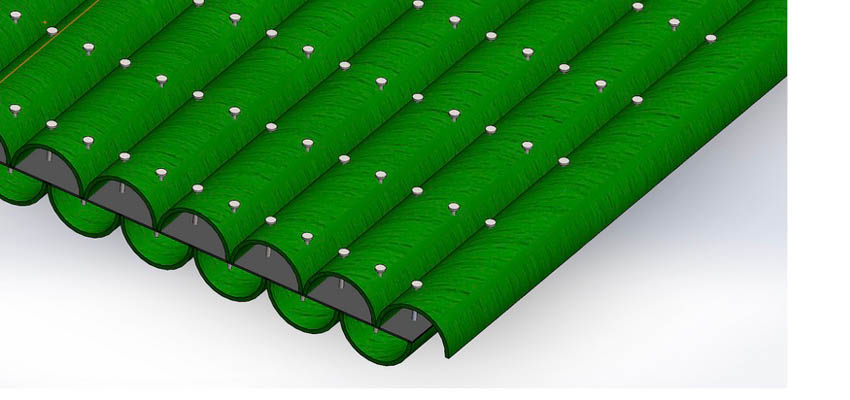

During the semester, we developed an initial prototype for a bamboo roof consisting of a roofing sheet nailed between two half-culms of bamboo.

We decided to make this roof in practice, and compare it to a more traditional half-culm roof design.

From our initial inspection, we suspect that our design may last longer, as it covers the more vulnerable inside part of the bamboo with the asphalt roofing sheet. However, this potentially comes at the cost of

January 14, 2024

Although the structure we were working on for the week didn’t use concrete pillars, the Auroville locals explained how we could create them for use in larger structures. In a traditional building, steel reinforcement bars are used to increase the tensile strength of the concrete pillar. Their design replaces the steel frame with a bamboo one. We began by splitting and cleaning bamboo culms. Long, thin, bamboo culms were used as the main reinforcement for the pillar. At evenly spaced points along the frame, steel roofing ties were used to attach split segments of bamboo to the frame and keep it held together.

The locals dug a hole in the ground where they wanted to place the column. In this case, it was to be used as structural support for a bridge. They mixed cement, sand, water and gravel to create concrete and poured in a small amount. Then, they assembled a steel mold for the column and applied oil to it to prevent the concrete from sticking to the mold. The frame was then placed within a metal form, and concrete was poured to fill the molds.

More information

MIT D-Lab class: D-Lab: Development

Contact

Libby Hsu, MIT D-Lab Associate Director of Academics