Some brief context before jumping in

I briefly mentioned some details on this in my last post, My journey through MIT D-Lab to Moving Health, but I’ll provide more of an explanation here.

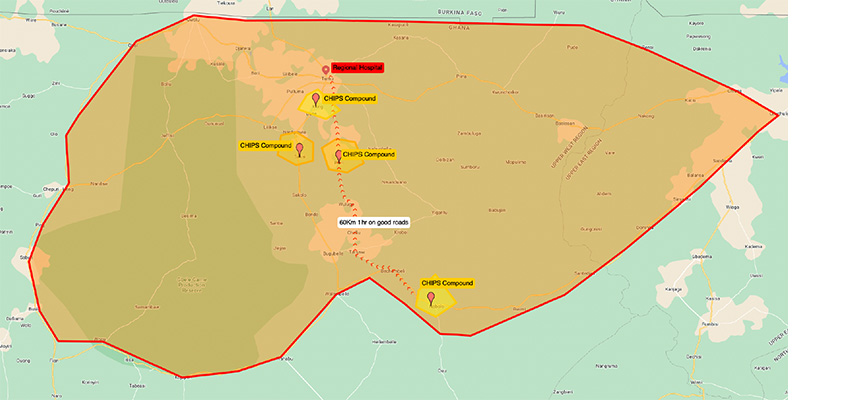

In Ghana, the healthcare system is very different than it is in the US. At the local level you have what are called “CHIPS compounds” which are community health centers where you can receive basic care, and deliver a baby without complications. If you need more care than the CHIPS compound can provide you’re referred to the “regional healthcare centers” which are father away, serve larger areas, and have more facilities. Other upper referral levels include the district hospitals and teaching hospitals which have even more specialized care but are rarer.

Many times, in life-threatening conditions, people need more care than the CHIPS compounds can really provide which means, at a minimum, they are looking at regional healthcare centers. These are often multi-hour drives from the villages, partially because of distance, partially because of road conditions. Traditional ambulances cannot traverse the terrain leaving many to arrange their own transportation. It’s an uncomfortable and dangerous experience, and many don’t make it to the care facilities in time.

Touchdown, and the adventure begins

There were three places we’d mainly be working while in Ghana — Kumasi, Accra, and Tumu. And all three were pretty foreign to me.

Accra was where a lot of electrical design work got done, definitely interesting but not so relevant for this post. We were working in an office and it felt similar to my time in India despite the significant cultural differences. The air smelled the same as Calcutta (maybe that’s a weird thing to say), and the architecture felt familiar.

Kumasi and Tumu were more interesting, I’ll get into that now.

seaside cliff. When built, the castle was the center of the Dutch slave trade and seeing it produced a somber feeling and a powerful reminder of the impacts of colonialism. Photo: Aditya Mehrotra

Naturally, I quickly made a fool of myself

I’d stepped out on the balcony of my second-floor room at the Nurom hotel in Kumasi one evening and closed the door behind me. I wanted to experience the smells of the city, and the weakening sun. I’d left my phone inside, I turned around to get it to take a picture, and I realized the door had no handle to let me back in. I handled the situation with grace.

“#*^!@$, me.”

I was heavily considering jumping into a bush until a street hawker selling water wandered by. I called to her — she looked at me bewildered as I begged her to get the hotel manager from the lobby. The guy came out, rolled on the floor laughing for a few minutes, and then came up and let me back into my room.

This experience made me think a lot about how I was approaching being here, in Ghana. Despite the fact that I’d taken two D-Lab classes and felt fairly ready for field work, this was the moment I learned the depth at which we carry our previous assumptions and the effect they have on our actions. It’s a simple, stupid example, but it reminded me that in this new place I was a stranger, and I’d have to step back, think, and proceed with caution not just for safety, but in my work as well.

Suame Magazine is the machine shop of Ghana, yet I still felt like a stranger

I like to spend most of my free time in a machine shop—my favorites at MIT being the D-Lab Workshop, N51’s Area 51 shop, MITERS, and MIT’s LMP. And my sincerest apologies to all, but they have nothing on Suame Magazine.

Suame Magazine is an industrial region in Kumasi in the Ashanti region of Ghana, and it’s where dying cars go to be reborn. It’s around 1,300 acres and home to over 200,000 artisans and crafts-people. Every artisan has a specialty from injection molding to machine design, and from sheet metal forming to bending. There are shops that sell V8 engines, springs, car doors, suspensions, tools, lights, gears, and bearings the size of me. It was candy-land.

But despite being inside a mechanical engineer’s dream, it was also truly the first time I’d ever felt… out-of-place? People stared, children pointed, and one guy even greeted me by saying, “Nǐ hǎo,” (I guess because he didn’t know what else to say). “Omamfrani,” someone muttered as we were walking back to the hotel one evening. Emily Young, Co-Founder and CEO of Moving Health and my instructor at D-Lab for the Design for Scale class looked at me: “It means outsider,” she said.

The gentleman at the bearing shop took a different approach, however. After learning I was an American, he decided for the next five days he would greet me by crossing his arms across his chest and giving me a solid — Wakanda Forever.

A whole new world (and its associated dynamics)

Emily is also an American and and this was the subject of many conversations. “One thing you’ll have to be careful about,” she said as we were taking a walk one evening, “is that people are just going to listen to you, and that’s a dangerous thing.” I experienced this first-hand. In group engineering discussions, often I’d bring up an opinion and the group would fall silent as I was explaining and at the end no one would disagree (at least initially). It was difficult because MIT got me used to the very feedback-driven approach to technical conversations where we’d have a good old fashioned argument and the project would be all the better for it.

Emily explained, “There are years of history to consider here, the impacts of colonialism run deep and often there’s an assumption that you just know ‘better’ being from the United States, whether that’s true or not.” She explained that this was something I’d need to be hyper-aware of, especially in these early stages where I was still learning about the project, the context, and the problem we were trying to solve. During technical conversations, Emily often only spoke at the very end after taking time to hear everyone’s opinion before making a decision. I learned to do that too.

But history can be more surprising if you look even deeper, and this was another conversation we had that I’ll summarize here. The NGO world really became formalized after World War II especially after the founding of the United Nations (see NGOs, Development, and Dependency: A Case Study of Save the Children in Malawi), but there’s a really interesting discussion on cycle of dependence to be had here.

Many of the nations (if not all of them) involved in WWII were colonizers, and during this period, many of their colonies were also gaining independence after long periods of being used as raw material, resource, and labor sources for the controlling powers. India gained independence just two years after WWII ended and Ghana just 10 years later. The term “NGOs” was coined as a part of the UN Charter’s Article 71 in 1945.

Not to be too blunt or to oversimplify the issue, but essentially what was happening during this time is that these colonizing countries had spent years stagnating development and removing resources from many of the countries that are now “in need.” Then, after being removed from power through a series of revolutions, countries like the US, and Great Britain established NGOs to essentially counteract the effects colonialism had on these nations. These countries were very much part of the problem, and now wanted to be the solution. The Declaration of Human Rights was also written at the founding of the UN in 1945 but was written mostly by countries that had committed rights violations rather than countries that had their rights violated.

If you take this as context, you can start to understand a story Emily told me of an African entrepreneur who said, “NGOs are the problem here in Africa” and why, in his opinion, we should invest in local talent and home-grown entrepreneurs that are building solutions to these problems rather than international NGOs no matter how local and focused their work is. There’s a stigma against NGOs in these countries that people often aren’t aware of. This was incredibly interesting to me and brought up many related conversations about nonprofit, for-profit, and hybrid company structures in the field of international development.

We shattered the front-left wheel of a Mitsubishi Outlander

To get to Tumu we first had to take a plane to Wa. It was a small, Bombardier Q400 turboprop and we didn’t really know if it was ever going to arrive. Generally, not many people travel by air between Kumasi and Wa usually because of how expensive it is to fly. There’s a single airplane that flies this route operated by a small airline, so if they don’t have enough passengers to make up for the fuel costs, they simply don’t take off.

The flight wasn’t long, but the drone of the propellers made it hard to nap or focus so I chose to look out the windows at the landscape. Trees and small communities connected with dusty dirt roads littered the landscape below. I was really hoping to see a giraffe or lion but we were too high up and in the wrong place geographically. When we landed in Wa, Isaac (the country director for Moving Health in Ghana) told me we still had a three-hour drive to Tumu and that it would be an uncomfortable experience for me.

We strapped our bags to the top of the Mitsubishi Outlander and got in the car. We’d been driving for about half an hour and our driver was feeling the need for speed. Sunglasses down, riding into the sunset, dodging potholes, and me holding my stomach in the back—I get carsick easily. The first little bit was OK as it was on tarmac and then we started hitting the dirt roads: since it was the rainy season they were worse than usual because the rain washes away a lot of the structure. Sometimes we’d try to dodge a particularly poor part of road and miss. This went horribly wrong pretty quickly.

There was an ear-splitting sound of metal smashing against metal, the car jerked forward and backward, and the driver made a pained face and the car slowed down. As we rolled to a stop, I could feel the front-left tire bouncing more than usual. We got out to asses the damage. The following conversation was in Sissala, and went something like this:

- “Can we make it to Tumu?”

- “With that rim?”

- “I’m thinking, no…”

- “Do we go back?”

- “Not sure we have a choice. If we get stuck out here at night, not safe.”

As the car limped back to Wa, I considered a few things. This car was a purposebuilt 4x4 off-roader, we weren’t going that fast during the rough parts, and this road still managed to shatter part of the wheel package. Not only that, Isaac told me this was one of the better roads in the upper-west region of Ghana as none of them are regularly maintained by the government (the small population doesn’t buy enough votes for them to care).

Not ideal for sure, but consider making this journey on this road on the back of a motorcycle for three hours while on your way to deliver a baby likely with complications. This was the moment I truly realized what these communities were up against.

We built an ambulance during a power outage

Now for some character introductions, enter Ambra, Sufiyanu, and Shedika. Ambra and Sufiyanu are the project’s lead engineers. They live in Tumu, one of the communities where we would be implementing the ambulances. Both have relatively little formal training but that didn’t stop them from being some of the best fabricators I’d ever met. Shedika is roughly my age and is a student at Asheshi University studying mechanical engineering. She is from Tumu as well, an intern like me, and strong-willed focusing on giving back to her community.

We had a week and a half to build an ambulance. Sufiyanu was tasked with the patient compartment, Ambra the driver’s compartment, and me and Shedika the stretcher that would go in the ambulance. And as is the case in most engineering projects, Murphy’s law applied: the power went out.

The tasks for the day involved a lot of cutting and welding the main frame of the ambulance. Most of our tools were corded because we needed the extra power. As I sat down and waited for the power to come back on, Sufiyanu approached the situation differently.

I heard a scraping sound and looked up to see him dragging a diesel engine he’d just yanked out of a shed into the clearing where we were working. He and his apprentices set about bracing it with some steel pipes and attaching a 15kW electric motor to it with a belt. They hooked up the welder to the motor and two of them held the machines apart to create sufficient belt tension. They started the engine and used the power generated by driving the motor to weld the motor to the steel frame of the engine. They took their hands off, and the creation ran on its own.

Just as Sufiyanu had finished re-inventing electricity, the power came back on. My attention turned to Ambra.

I don’t think I ever saw Ambra pick up a ruler or tape measure the entire week. He’d walk over to a pile of metal, stare at it for a few minutes, and then he’d just start. Cutting, bolting, and the only measuring tool he used were his eyes and pieces of metal he’d cut himself. He built an adjustable thickness bending machine in less than four hours, and then moved on to building the drivers

compartment.

Watching them work taught me so much about what engineering could be. They didn’t take the math-driven approach to engineering that we’re so often taught. They used experience and intuition. They knew materials were strong enough by trial and error, and their designs were minimalistic and incredibly creative. That’s not to say one approach is right or wrong, they’re just different. It made me

realize something that I think isn’t taught often enough. Engineering isn’t math and math isn’t engineering. Engineering is fundamentally about problem solving and how you choose to solve that problem is up to you. Mathematical foundation is of course important and good to know, but it’s not the end-all-and-be-all. Knowing when to use modeling and mathematics versus the “build it and break it” technique is just as important.

The final ambulance design will be released in a product launch later this year. Follow @moving.health on Instagram for updates! Moving forward, the organization will expand to deploying ambulances in most of the communities in the upper-west region to give more people access to emergency transportation when needed most.

Just some closing thoughts from the back of a tuk-tuk

Shedika and I spent a lot of time in the back of Paul’s tuk-tuk riding between the hotel and the workshop. This gave us ample time to reflect. She told me about her future plans (summarized).

“I think education is a real issue. So I didn’t know about engineering until my physics master told me in senior high school. I think people don’t know about the opportunities that are out there and that you can be an engineer as a girl and you can help your community. I want to start a NGO for students in my town, and help them learn about engineering and how it can help make our community a better place if we all work together. I’m thinking about even being an MP for my region, and then help to make the community better.”

I turned my camera on and started to record, but that’s for next time.

Facts from Ghana

- Women own shops in Suame Magazine, many of the tools stores and material purchasing centers are women-owned and operated.

- The Dutch government employed the workers of Suame Magazine to build an off-road vehicle in 2012. They made it, out of 100% recycled material (link).

- This YouTube video (courtesy of Diane Li) www.youtube.com/watch?v=GAoK4XjssrM

- Ghana is the second largest producer of Gold in Africa and the second largest producer of Cocoa in the world. It also sits on top of an oil reserve 20.5 times its own annual consumption and recently Lithium stores have been discovered below the country’s surface.

- The Ukraine war is directly affecting northern farmers. As oil as gas prices increase the cost of living does too, the price of crop doesn’t increase meaning these farmers are earning the same amount of total income during a time of greatly increased living expense.

- Couple 5 with climate change. During this time of the year, it can rain up to three times a day in the northern regions of Ghana. For us, it rained twice in two weeks. I passed by a 1-2 acre corn farm in August during a time the corn was supposed to be 5-6 feet tall and ready for harvesting. It was barely a foot tall, the farmer had lost his entire crop.