Getting started

Through the D-Lab: Development class, we learned about local waste management and sustainability efforts in Cochabamba, the fourth largest city in Bolivia. The previous year, D-Lab established a connection with the Ecorecolectoras – a women-led association of waste pickers in Cochabamba – to support their important work to protect the environment and provide decent jobs. We built on this connection during class and met remotely with the association leaders as well as students and faculty at the Applied Technology Research Center (CITA) at the Higher University of San Simón (UMSS), a local university partner.

The project that the three of our organizations are working on is around the theme of Kutimuy. Kutimuy is a Quechua word meaning “return” and relates to the goal of fostering a circular material economy in Cochabamba. This sustainability goal significantly involves the contribution of the Ecorecolectoras and similar groups, so ensuring they have efficient tools and ample resources is key. Before embarking on our trip to Cochabamba during IAP, we discussed with the Ecorecolectora the challenges they face in their daily operations – which we would better understand in person.

The primary goals of our trip were to:

- witness the work and organization of the Ecorecolectoras

- meet stakeholders that impact waste management and upcycling in Cochabamba

- support the Ecorecolectoras through a Creative Capacity Building workshop at UMSS – including advancement on technologies and new business plans.

Below you will find Part 2 of a two-part blog post series. Part 1 can be found here.

A collaborative workshop

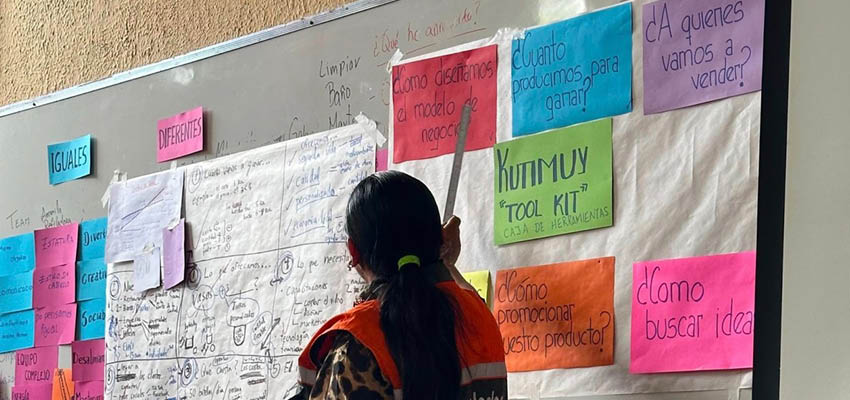

The second week of our trip consisted of a Creative Capacity Building (CCB) workshop, which follows a participatory design methodology from MIT D-Lab. The goal of such a workshop is to empower the participants to develop and test solutions to particular problems that they face. Current challenges that the Ecorecolectoras encounter in their work established the basis of our CCB workshop. How can we use technology and collaboration to improve the association’s livelihood? Over five days, the Ecorecoletoras, Higher University of San Simón (UMSS) students and faculty, and our MIT D-Lab team devised and designed answers to that question.

The workshop took place in a classroom at UMSS. There were 36 participants: 14 Ecorecolectoras, 10 students from UMSS, seven faculty members and staff from UMSS, and five of us with D-Lab. The initial sessions included icebreaker activities – such as coming up with group songs and playing variations of rock-paper-scissors – for us to meet and get comfortable working with one another. We also had coffee breaks and lunches together. Four groups were formed, each of which focused on a different project.

Before starting the projects, we wanted everyone to get into the design mindset through three exercises. First, we each received a glass mug to paint on – this activity showcased many talents and creative ideas. Second, we competed in groups to use just four sheets of paper to create the strongest (i.e., crack-proof) container for an egg… the final tests got a bit messy. Third, we created plastic bottle cutters based on a model presented by the UMSS instructors. We assembled a few simple materials to create a relatively effective means of turning plastic bottles into meters-long strips of plastic filament, which can be further shaped by running the strips through a hot glue gun. This upcycled plastic can be sold to businesses that need packaging or other fastening material. These preliminary exercises were helpful in stirring our imagination and getting used to some tools before commencing the projects.

Challenges to tackle

To provide context for the workshop projects, our conversations with the Ecorecolectoras revealed that their needs include improving transportation for materials and expanding into new markets. The first need led us to consider technology that makes material storage more efficient. The second led us to explore potential markets for recycled glass enabled by affordable machines.

Currently, glass bottles are a common form of waste found in Cochabamba, but glass recycling companies are only willing to buy glass bottles at a low price point (about 0.25 USD per kilo) due to the high cost of cleaning and processing such waste. Additionally, most of the Ecorecolectoras lack the financial resources to deliver their collected waste to recycling companies, so they often have to pay a “middleman” for transportation, decreasing their revenue. Thus, the Ecorecolectoras had the idea of repurposing, designing, and selling collected glass as upcycled products, which bypasses both of the aforementioned extra costs (transportation and materials processing). Before the workshop, the primary challenge for implementing this venture was finding low-cost, quick, and reliable ways to cut through glass bottles and smooth the edges of the cut pieces. Another barrier was devising a sustainable business model, informed by customer insights.

Making waste transportation more efficient

Our first project was to motorize an existing machine to compact plastic bottles and aluminum cans. The machine allows for better storage of bulk materials that need to be transported by the Ecorecolectoras for sale, often to far distances and with minimal space. By adding a motor, the machine can be more accessible, time-saving, and safe for all users. A takeaway from the experimentation was that adding a 1.5 hp motor to replace the manual crank allows the machine to operate at an advantageous 50 rpm even when multiple bottlenecks are present.

Enabling a new life for glass bottles

Our second and third projects sought to transform glass bottles. One machine would cut glass bottles of varying shape and thickness while the other would file the resulting sharp edges. Access to such technology – and involvement in its design – is essential for the Ecorecolectoras to pursue their glass upcycling goals.

The second project, the glass cutter, needed to be versatile and safe. Standard cutting tools like electrical saws may be prone to shattering glass or too expensive. An alternative cutting method is thermal shock: the desired cut location is heated and then the glass is placed in cold water so that rapid temperature change causes a fracture. We devised a prototype involving thermal shock administered by a heating element that’s replaceable for under 2 USD. The heating element was held by brick (for its insulating properties), with an iron frame supporting the machine. Some of our team members learned to cut and weld metal pieces for the first time. By involving the Ecorecolectoras in the entire process, we hoped to enable them to repair the machine in the future.

To cut a bottle, we would rotate it along the heating element for between 15 seconds and 2.5 minutes depending on thickness (overheating increases the chance of fracturing). Forming even cuts can be a challenge so we experimented with making an initial incision with the diamond-tipped cutter and rotating the bottle more slowly. These techniques helped and we also eventually had the idea to deepen the rivet in the brick where the heating element was placed to concentrate the heat.

The third project, the glass filer project, was actually working on improvements to an existing machine designed to melt any sharp glass edges resulting from a cut or fracture. This process renders the edges smooth, making glassware that’s safe to use and marketable to consumers. The original design involved four natural gas burners in a circle that could point flames at the edge of a glass cup to smooth it. However, only two of the burners worked, and keeping the machine steady while working with it to heat the glass evenly was challenging. Therefore, this design aimed to hold the glass and burners stable, enabling the machine to work consistently for glasses of different heights and shapes. The new design included a motor to quickly rotate the glass, adjustable pins to hold the glass in place, and an spring-powered arm holding the burners that moves according to the shape of the glass.

Developing a Kutimuy business strategy

Our fourth project was to develop a business model for glass upcycling. We discussed market demand for glass products, based on our previous meetings, as well as production capabilities. The glass cutter and filer that other groups were working on would be essential tools for the business. We outlined a 6-part business model after brainstorming and diagramming sessions. It included: [1] detailing the products, [2] understanding potential clients, [3] calculating production costs, [4] listing technical, financial, and other internal needs, [5] planning client engagement, and [6] estimating projected earnings. As such, the strategy is multi-pronged and factors in marketing, branding, impact evaluation, and price analysis. We supplemented the business model diagrams with a toolkit that included a spreadsheet to estimate balance and growth, contacts of potential clients, a list of skill-building resources, ideas for branding and marketing, and images of precedents for some inspiration.

We think that this development of a business model for Kutimuy glass upcycling was an important starting place. The process is still iterative and must be adjusted based on new information and plans. Also, some of the fundamental concepts we discussed are transferable to various endeavors that the association may pursue.

Moving forward

Overall, we found the workshop to be successful, laying the groundwork for fresh innovation. We enjoyed building prototypes together and getting to see concepts materialize over just a few days. All four projects were driven by clear needs, preferences, and ideas of the Ecorecolectoras. This user-centered process is precisely the purpose of Creative Capacity Building.

We hope to see how the Ecorecolectoras progress in their business aspirations over the coming days. We thank all of our new friends in Cochabamba for their generosity during our trip. And we look forward to future collaborations!

This is Part 2 of a two-part blog post series. Part 1 can be found here.

About the authors

Daud Shad is currently a second-year master's student at MIT in city planning, with a focus on international development.

Jeremy Zhou is a third-year undergraduate student at MIT studying mathematics and economics.

More information

MIT D-Lab class: D-Lab: Development

MIT Program: Inclusive Economies

Contact

Libby Hsu, MIT D-Lab Associate Director of Academics