"After this experience, I hope to continue in this field of work and contribute to a movement that welcomes refugees with open arms."

There are about 3,800 unaccompanied refugee minors in Greece. In 2015 there was a huge influx of Syrian refugees passing through Greece from Turkey with hopes of continuing on and seeking asylum in Western European countries that had opened their borders to refugees. Refugees from Iraq, Afghanistan, and Iran also began crossing into Greece with the same goal in mind. In 2016, the European Union and Turkey made a deal that effectively closed their borders, which stranded 60,000 refugees in Greece. Of that 60,000, over 3,000 were unaccompanied minors.

MIT D-Lab team heads to Athens to work with Faros, an NGO working with refugee youth and families

During January, as part of MIT's Independent Activities Period (IAP) term I had the opportunity to travel to Athens, Greece with a team of MIT D-Lab staff and students: Humanitarian Innovation Specialist Martha Thompson, Designer Heewon Lee, MIT IDM students Sabira Lakhani, and Susana Tort, MIT undergraduate students Alexandra Shade and Franklin Zhang, Harvard College undergraduate student Ivraj Seerha, and high school graduate Tal Moss-Haaren. During our time there we worked with a Greek NGO named Faros at their vocational and innovation training center called the Horizon Center. The Horizon Center aims to promote and build confidence in refugee youth through design and training in skills including tailoring, woodworking, and CAD/3D printing. The center uses D-Lab’s Creative Capacity Building (CCB) methodology in its design training and has been working with D-Lab’s Humanitarian Innovation program for the past year and a half.

Workshops for refugee youth at Faros's Horizon Center

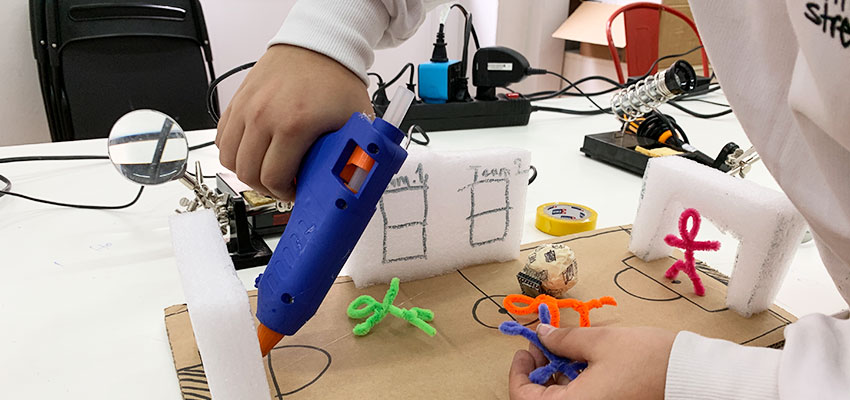

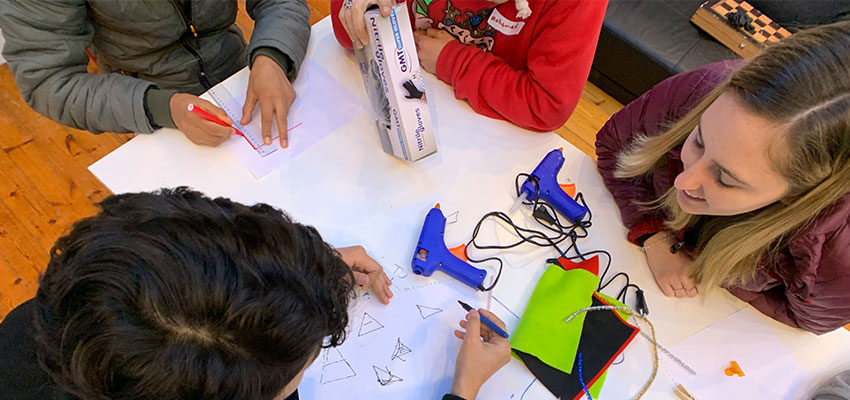

Over the course of nine days, we taught a workshop at the Horizon Center to refugee youth ages nine to 18. We taught the students skills in woodworking, soldering, silk screening, Adobe Illustrator, CAD/3D printing, breadboarding, and Arduino in the format of three different projects. The first project combined design and silk screen printing. We asked the students to design a logo to print on a t-shirt that they could wear as a soccer jersey. (We wanted to incorporate soccer into the projects because the students all love to play, and organize games every Thursday.)

First, they sketched some ideas on paper and then we taught them to use Powerpoint or Adobe Illustrator, depending on the level of their computer skills, to design their logos on the computer. It was amazing to see how quickly they picked up a computer program that was completely new to them. After teaching them the basics, they all wanted to explore the program and learn how to use more tools. Some students created original designs and others made the Nike or Adidas logos. Regardless of what their design was, they were excited to design a logo and took ownership of making every detail perfect. The day that we finally printed the logos onto T-shirts was hectic, but filled with excitement. The students shared logos and even printed multiple on their shirts. For the rest of the workshop, many students wore their shirts under a sweater.

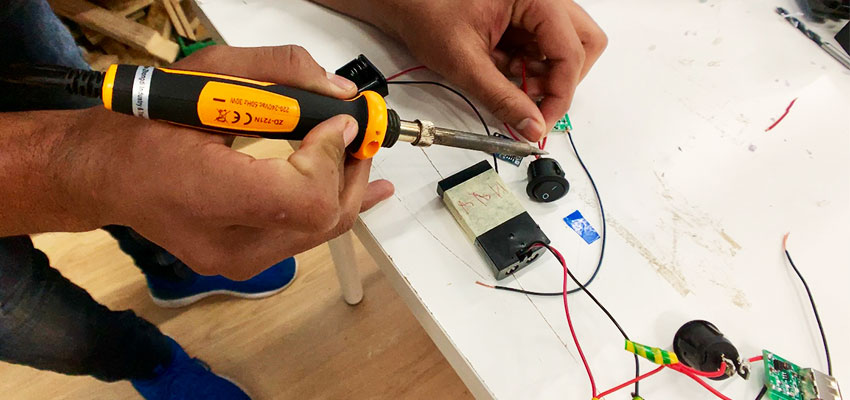

The second project incorporated sketch modeling, soldering, CAD, and 3D printing. This project was to build a power bank and design and 3D print a case for the power bank that also served as a phone stand. We taught the students about electrical circuits and the different components including the battery, switch and output. We also taught them to solder red and black wires to the USB boards to create their own circuit (power bank). When they finished, they immediately wanted to plug their phone in to test if it worked. When it did, their faces lit up with excitement and they yelled “Teacher, look! Working!.” When it didn’t, they were determined to troubleshoot the problem and try again.

We also introduced them to sketch modeling to design the cases for their power banks. Sketch modeling was a hit - it allowed the students to be creative and make designs unique to their personal preferences, as well as actually demonstrate their ideas instead of trying to verbalize them or draw them on paper. After they created some sketch models, they presented their ideas to the rest of the group and gave each other feedback. We then taught them how to put their final design into a CAD program called 3D build. Finally, it was time to 3D print. When the students got to hold their finished products in their hands, they were overjoyed and so proud of their work. Many students came to the center early and stayed late in the workshop to put the finishing touches on their cases.

The final project was to build a scoreboard for the students to use when they played soccer. We split the students into teams: one team worked on the electrical and Arduino component of the board and the other designed and built the structure. The team that worked on the electrical component learned to breadboard and use Arduino to make the numbers on the scoreboard from LED lights. The team that built the structure used sketch modeling to decide on a final design for the scoreboard and then used woodworking skills to measure and saw each part and drill the pieces together. The final product was a rectangular box with LED numbers on the front and a hinged door on the back. The front was covered by corkboard so that the team names could be pinned above the numbers for each game. The box also had a detachable shade on the front for sunny days and a strap on the top to allow for easy transportation. There was also a power/reset button on the top of the box and buttons on either side to change the numbers when a team scores a point.

Life for youth refugee in Athens, Greece

This trip was an all-around amazing experience. I didn’t know what to expect when working with youth that had been through such traumatic experiences. Some of the boys that we worked with were unaccompanied, meaning that they were in Greece without any family members. Others were accompanied by a parent or relative. The unaccompanied children were either sent ahead of their families to go to Europe, find a job, and send money home, or were separated from their families on their journey to Greece. In some cases, these kids are orphans. The journey they make, mostly from Syria, Afghanistan, or Iraq to Greece is dangerous and exhausting. Most refugees first arrive in Turkey, having traveled there by foot, bus, or train. They then leave Turkey and travel to Greece, usually by boat. Their intended final destinations are other European countries, but many people become stuck in Greece due to legal restrictions. The only legal way to leave Greece is by being reunited with a family member in another country - but you are only eligible for reunification if you are under 18 years old. In addition, the process of applying for reunification and having your application reviewed is long and difficult. This leaves many kids stuck in Greece, holding on to the hope that they will be approved to leave before they age out. This also drives many young people to attempt to enter other European countries illegally via human traffickers. While in Greece, these kids are either living in shelters, squats, or on the streets. There are close to 4,000 unaccompanied refugee minors in Greece, but only about 1,100 to 1,200 beds in shelters, leaving 900 kids in camps and many without proper care and shelter.

The best students I could have asked for

Despite these circumstances, the youth we worked with were the best students I could have asked for. Yes, there were moments of distraction and chaos, but that is to be expected when working with 25 to30 young boys. Their excitement and eagerness to learn drove us to modify and remodify our lesson plans, spend our evenings discussing how to improve our teaching, spend Saturday at the center to keep it open for the kids, and take night shifts 3D-printing their projects. Our investment in this workshop was met and multiplied by the students.

"We want peace"

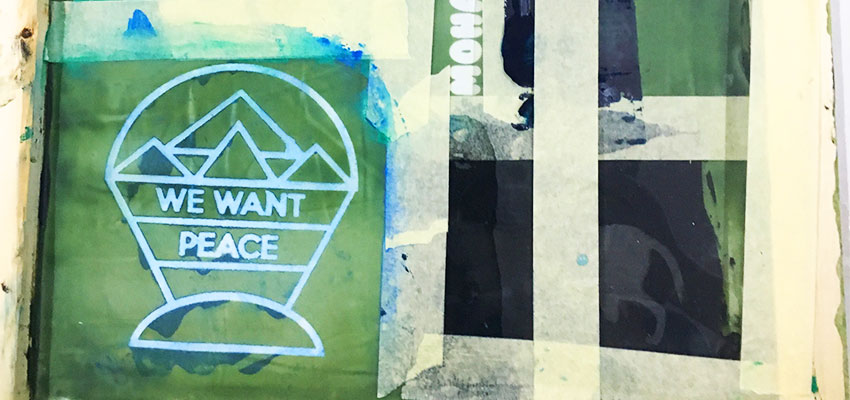

One project that I especially enjoyed was logo design and silk screen printing. During the logo design session, one student wanted to draw a cheetah as his logo. He asked me to look up a picture of a cheetah on my phone and then proceeded to spend 45 minutes carefully sketching. When using Adobe Illustrator, he tried many tools until he found one that allowed him to perfectly draw the outline of his cheetah. Another student that I worked with through the entire process of this project created a design that touched us all. He first sketched two designs on paper and asked me, “Teacher, which one is better?” One sketch was of a dove with the words “we want peace” written across it. The other was of a lantern patterned with mountains and the same words, “we want peace,” written inside. I told him that both were very good and that he should decide - he went with the lantern logo. Those three simple words stayed with me throughout the rest of the trip, and will forever. That is all these kids really want. Peace. Peace, so that they can learn and grow to their full potential. Peace, so that they can find stability in their lives. Peace, so that they can one day return home.

"Their home countries and cultures are at the core of their identity"

Another thing that struck me was how proud every student was of where he was from. They all wanted to tell us where they were from and ask us the same. Their home countries and cultures are at the core of their identity, and something that they are clinging on to. A few boys that opened up to me about their hope for the future talked about their hope of returning home and pursuing a career. The refugees who have traveled far and long to Greece have not made that journey just to move to a “better” place. They have gone there, and to other countries, to escape unlivable situations. They did not want to leave their homes.

I think that this is what many people fail to understand when talking about the refugee crisis. On this trip, while meeting other organizations and people who work with refugees, I often heard terms such as “economic refugee” and the fact that many people, from countries such as Iraq, are not legally considered refugees. This promotes the false idea that these people left their homes just to move to a country of greater wealth, when this simply isn’t true. They are fleeing danger, not poverty. There is a great need for efforts to assimilate refugees and promote understanding among Europeans living in places with refugees. After this experience, I hope to continue in this field of work and contribute to a movement that welcomes refugees with open arms.

About the author

Caroline Morris recently graduated from Wellesley College and is originally from Atlanta, Georgia. She has experience with project development, prototyping, conducting co-design workshops, and traveling abroad for field work through the MIT D-Lab, where she has taken four courses: D-Lab: Development, D-Lab: Earth, D-Lab: Design and Design for Scale. Caroline also "UROPed" at D-Lab and traveled to India three times to conduct research for a D-Lab xylem water filter project. She is passionate about public health policy, international development, biology and women's empowerment. Caroline also loves to run and spend time by the ocean.

Related

For an additional perspective on this trip, read Alexandra Shade's blog post!

For more information about the MIT D-Lab Humanitarian Innovation Program

Martha Thompson, MIT D-Lab Humanitarian Innovation Specialist and Instructor