There are about 3,800 unaccompanied refugee minors in Greece. In 2015 there was a huge influx of Syrian refugees passing through Greece from Turkey in the hopes of continuing on and seeking asylum in other Western European countries who had opened their borders to refugees. Refugees from Iraq, Afghanistan, Iran also began crossing into Greece with the same goal in mind. In 2016, the EU and Turkey made a deal that effectively closed their borders, which stranded 60,000 refugees in Greece. Of that 60,000, over 3,000 were unaccompanied minors.

In January, during MIT's Independent Activities Period (IAP), a team of MIT D-Lab staff and students traveled to Athens, Greece to work with Faros, a Greek NGO supporting refugee youth and families. The team include D-Lab Humanitarian Innovation Specialist Martha Thompson, Designer Heewon Lee, MIT IDM students Sabira Lakhani, and Susana Tort, MIT undergraduate students Alexandra Shade and Franklin Zhang, Harvard College undergraduate student Ivraj Seerha, former D-Lab student and recent Wellesley grad Caroline Morris, and high school graduate Tal Moss-Haaren.

Read on for Alex Shade's reflections on the trip!

I want to go back

I want to go back. Going into this trip, I already knew that teaching kids was something I really enjoyed doing, but I also knew this situation was going to be different because the circumstances were very different. It was such a unique learning experience. I learned about myself, I met a lot of really cool people who are doing really meaningful work, and I learned a lot about the refugee crisis in Greece, which isn’t talked about nearly as much as it should be.

Working with boys from Afghanistan, Eritrea, Iran, Iraq, Pakistan, Syria, and other countries

I expected most of the kids we were working with to be Syrian, because the Syrian refugee crisis was so heavily publicized, but the kids we worked with were primarily Afghani. We also had boys from Pakistan, Iran, Eritrea, Iraq, and a few other countries. Most of them didn’t speak Eenglish. Most of them spoke Farsi, but others spoke Arabic, Urdu, or Hindi. Before we actually worked with the boys, we had a long meeting at the UNHCR office where we were given a pretty detailed history of the current refugee situation in Greece and the current challenges. It was honestly a really sad meeting. Currently, leaving Greece to seek asylum in another European country is nearly impossible. So many people are living in horrible conditions in refugee camps in Greece and all of the camps are overcrowded because they weren’t created to be permanent housing. And of those who aren’t living in the camps, a lot of them are homeless.

Kids in limbo, Faros providing services

They aren’t legally allowed to have jobs without Greek work permits, which are really hard to get, especially if you don’t speak Greek. The refugee children aren’t allowed to legally work at all, so a lot of them are desperate for money and have been exploited by adults. This is why Faros was created, to provide a safe space for refugee youth and families with children. They go out and find unaccompanied minors on the streets, they have a shelter where they serve free food every day and provide a safe place to sleep; they offer psychological support, legal support, and access to social workers; and now they’re focusing more on education to empower the youth and equip them with the skills and confidence they’ll need to succeed in the future. This is where we came in to help.

The largest group D-Lab has worked with at Faros so far

In Boston we finished developing the curriculum, prepared all of the tools and materials we would need to take with us, and learned all of the skills that we were going to be teaching the boys. After we arrived in Athens, we met with Faros staff to discuss the curriculum and figure out some last minute details, but there were still a lot of unknowns that we wouldn’t learn about until the workshop actually started. We had no idea how many boys were going to show up for our workshop. Although we knew we were working with minors, we didn’t know the actual age range of the boys that would come (and teaching mostly 10 year olds is very different than teaching mostly 17 year olds). We also didn’t know if we were going to have the same group of boys or different boys every day. They weren’t at all obligated to go to the workshop, so if they didn’t enjoy what we were teaching, they might leave. One of our biggest unknowns that ended up playing a key role was whether or not we would have a translators each day. I expected we’d have to be flexible and be prepared to make changes, and we did. Our workshop ended up having 20 t-30 boys every day, making it the largest workshop D-Lab has done with Faros at their Horizon Center.

Motivation to learn, pride in their work

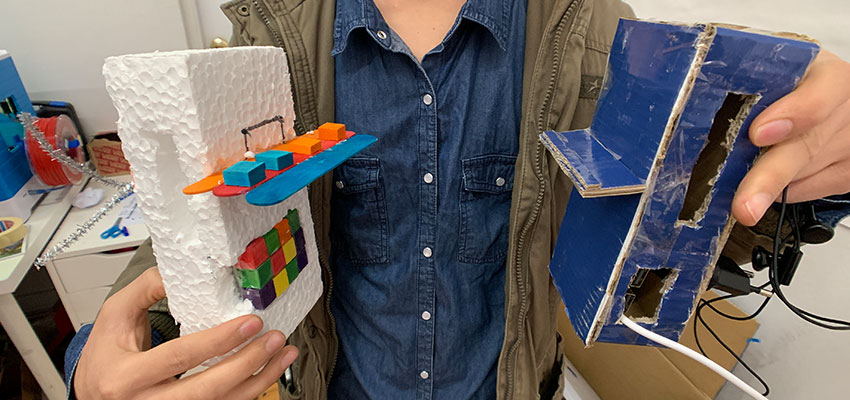

The boys were so great. They were so eager to learn and they took a lot of pride in their work and were so excited to show us their final products. We also realized pretty quickly that although they were excited to learn new things, it was incredibly important for them to be able to finish each project because it gave them a lot of personal fulfilment, so we restructured our plan to allow multiple groups to be working on different things at the same time. They liked the workshop so much that they would show up early to ask to start working on projects. Some of the older boys (who didn’t even go to the workshop) showed up early to hang out and play music and dance with all the others boys. We stayed late every day because they wanted to stay late to continue working. We even opened the center for them on a Saturday (the center is usually closed on weekends) and A LOT of kids ended up coming in. I was honestly just so impressed and very surprised. And yeah, it got a little crazy and hectic at times (15 young boys in a small woodshop full of potentially dangerous power tools is not the most relaxing environment), but they were having fun and no one got hurt. Every day of the workshop was pretty exhausting, but also undeniably rewarding.

Came for English classes, left wanting to be an engineer

One of my most memorable stories from this trip started a few days into the workshop when a new boy came to the center. He said he came for English classes (he must’ve gotten the dates wrong), but we convinced him to stay for the workshop anyway. At the end of the day he said “This was so great, when can I come back?” He came back every day for the rest of the workshop, and every day he stayed late and offered to help cleanup.

During the final project (the scoreboard), he was in my group of students and we were teaching them how to use switches and MOSFETS to light up LED strips on a breadboard. English isn’t his first language, and we were teaching relatively complex concepts, so at first he was really confused, but when we were in small groups and I explained it to him a few more times and showed him a working circuit, he started to understand and started working on his own. A few minutes later, he showed me his circuit and he was mostly right, so I showed him what was wrong and corrected it. I told him “the more practice you get, the more you improve at a skill,” and then while I was helping other students, I asked him to take his circuit apart and rebuild it to see if he actually understood how to make it by himself. He tentatively said “Ok, I’ll try,” and then 10 minutes later he showed me his circuit and it worked! He was really happy and then he started helping other students and showing them how to make it.

We were having a showcase on the last day of the workshop and I asked him if he would present for the circuits part of the project, and I could tell he was nervous (because he was kind of a shy kid), but he agreed. And at the end of his presentation, he thanked me personally for helping him and thanked all of the staff and said that this workshop changed his life and he wanted to keep making things and be an engineer and I could feel myself getting emotional.

Hard lives, new skills

I wasn’t expecting to get so emotionally invested so fast because we weren’t there for a very long time, but leaving was hard. We didn’t just show up, teach lessons and go home. We played little games with them, we ate lunch at the shelter with them every day and we got to talk to them and learn some of their stories. We learned that some of the kids left the workshop early every day because they were trying to claim beds for the night at other shelters. Some of the kids have been in jail because Greek police have been putting minors in detention centers in a poor attempt to get them off the streets. Some of the kids have lost their families. They’re only children, but they’ve already had such hard lives and it’s not fair. We got the chance to take part in a program that offered these boys a chance to just have fun and be kids and make new friends. And in addition to the physical projects that they made and got to take home, they got to learn new valuable skills, and that knowledge is something that no one can ever take away from them.

This experience was brief, but it was honestly a trip that I’m not likely to forget. I want to go back. I’m going to try to go back.

About the author

Alexandra Shade was born and raised in California and is currently a senior at MIT majoring in Mechanical Engineering with a concentration in Sustainable Development and Innovation. Through her engineering classes and personal projects, she has been able to pursue her passions for design, product development, product engineering, and international development. In the future she hopes to travel the world working with IDDS (International Development Design Summits) and supporting co-creation projects to help create low-cost, practical innovations to improve the lives of people living in poverty. In her free time, Alexandra enjoys hiking, reading, running, and working with children.

Related

For an additional perspective on this trip, read Caroline Morris' blog post!

For more information about the MIT D-Lab Humanitarian Innovation Program

Martha Thompson, MIT D-Lab Humanitarian Innovation Specialist and Instructor