|

|

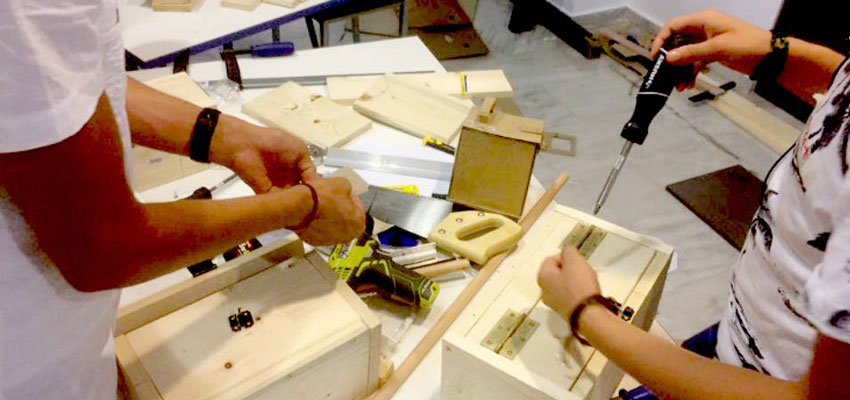

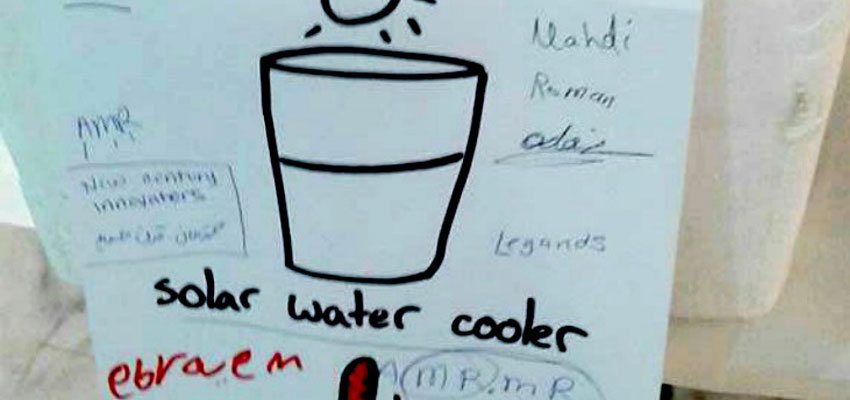

“We set out to help unaccompanied minors develop confidence in their ability to solve problems. Our model was D-Lab’s Creative Capacity Building (CCB) curriculum, which has been used in communities all over the world. Instead of outsourcing problem-solving to foreign teams of designers, CCB brings the design cycle to the people actually living a resource-poor or refugee reality."In late July, I went to Athens, Greece with a team of six students and instructors from MIT D-Lab, to introduce design to young refugees. We teamed up with Faros, a local organization that runs a day center and a shelter for refugees who are unaccompanied minors. Dan and Patricia Biswas, who co-run Faros, connected us with Maria Calafatis and Stavros Messinis at The Cube Athens, a nearby co-working space with a machine shop on the bottom floor. We set out to help unaccompanied minors develop confidence in their ability to solve problems. Our model was D-Lab’s Creative Capacity Building (CCB) curriculum, which has been used in communities all over the world. Instead of outsourcing problem-solving to foreign teams of designers, CCB brings the design cycle to the people actually living a resource-poor or refugee reality. The catch is that CCB trainings had only ever been run with adult participants in rural settings, so we had to work to make examples relevant.  The six-day workshop began with teenage refugees making hot-wire circuits to cut styrofoam. We later buried their designs in sand and showed them how melted aluminum could burn away the styrofoam and take its place, leaving a metal replica of the foam original. As a skill-builder and a design exercise, we asked the participants to design lockable boxes using only a limited allotment of wood. The task was designed to teach the value of prototyping, while encouraging creativity. The youth produced varied and rather beautiful designs with cardboard, then translated their designs to wood after learning some tool safety. Many of the youth came early in the mornings and stayed late into the afternoons, and would only reluctantly stop working on their boxes for lunch. Some ran into problems with measurement, (as it turns out, most lumber is significantly thicker than cardboard), or making angled cuts without a miter saw. An intricate design for an octagon box had to be scrapped in favor of something with more right angles. A triangle box did emerge, after a herculean effort by a very persistent participant and two dedicated facilitators. In the latter half of the six-day workshop, the youth chose their own problems to solve and worked through the entire design cycle in teams. One group demonstrated a solar-powered water pump to irrigate terraced orchards back in Afghanistan, using a miniature working model complete with origami trees. I facilitated a team designing a baseball cap with a fan directed at the wearer’s face, which became less dangerous with each prototype. Oh, the power of iteration! These youth are part of a group of 2,300 unaccompanied minors stranded in Greece. They fled their homes in Afghanistan, Syria, Iraq, and Pakistan, hoping to continue their educations in Europe, then were trapped when borders closed after the refugee influx of 2016. Some have been in limbo for two years, and more still arrive; some are waiting to be unified with family members in Europe, while many have no clear path out of Greece, but never wanted to stay here. One of the participants told me he’d left his family (already refugees from Palestine) rather than be drafted into the army in Syria. He asked if I thought that was cowardly. The truth is that these teenage kids are unbelievably brave and resilient. They’ve seen their countries torn apart, left or lost their families, lived in a state of perpetual uncertainty for years, traveled under dangerous conditions, been exploited, had their educations disrupted, and been almost completely overlooked by aid organizations until late 2016. But there they were, proudly explaining their projects at a public final showcase, and accepting participation certificates with huge smiles. It felt like watching them reclaim their identities as curious, ambitious young people — a self-image that may have been eroded by their refugee status.  |

While the rest of the MIT contingent left, I stayed in Greece to do followup. Now I’m running shop hours so the youth can work on personal projects, and teaching workshops to introduce new skills, like basic circuitry and soldering. I’ll stay on for the next few months, during which time I’ll develop and implement a curriculum to introduce design to youth who weren’t in the original workshop, and expand their skill sets with micro controllers, a CNC mill, and a beautiful miter saw recently acquired by The Cube. D-Lab is also hoping to continue the collaboration with Faros and establish an innovation center in Athens, where local Greek youth and refugees can share a space to work on projects. Many thanks to UGC, UNHCR, and D-Lab for supporting stability and empowerment for young people in such a transient situation.